By Lauren Heidbrink

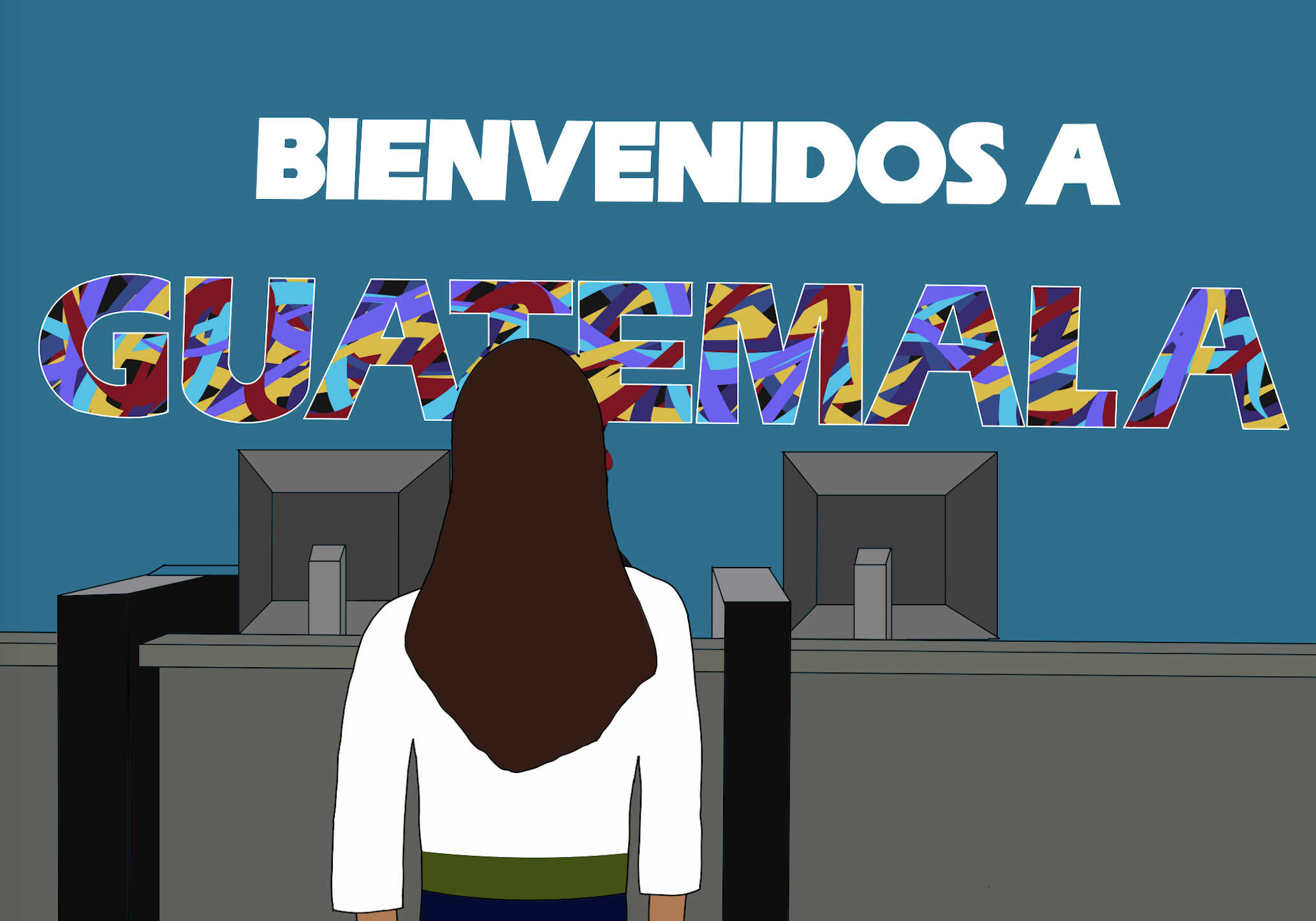

Camila was fourteen when she was deported from Houston to Guatemala. It was her first time on an airplane. When the chartered plane landed at Guatemala City’s air force base, guards hurried the children out, signed a few papers, and closed the doors without ever stepping foot in the country.

At the government shelter where I met her, Camila went without food or information as staff humiliate her Indigenous parents, who arrived after a fifteen-hour bus ride, told of her return only at the last minute. When Camila returned to her hometown of Pajapita, she hid inside for weeks. In her evangelical church, the pastor preached that deportation as a sign of weak faith: if she had believed more strongly in God, she would have made it. “Next time,” Camila told me, “I will pray harder.”

Camila’s experience is the reality of hundreds of children I have interviewed over the last decade—most of them Maya—who confront fragmented U.S.–Guatemalan coordination, long-standing anti-Indigenous discrimination, and no government support following return.

Last weekend, a federal judge temporarily blocked the Trump administration from deporting 600 Guatemalan children, some already on the tarmac. Judge Sparkle Sooknanan’s order underscored what years of research demonstrate: deportation does not mean protection, reintegration, or safety. For most children, it brings renewed vulnerability.

Eufemia, fourteen, recently returned to Guatemala after seven months in Office of Refugee Resettlement custody. Her mother in Long Beach explained, ‘If I come forward, immigration will deport me too. What will happen to my children here, and my family in Guatemala who depend on me to eat?’ The family had mortgaged their land to finance Eufemia’s journey after two failed harvests from drought and crop infestations. With their land and livelihood at risk, Eufemia weighed whether to try again.

En la tienda. Illustrated by: Gabriela Afable

Elder, deported at fifteen after a workplace raid in Utah, faced similar challenges. Back in San Marcos, his mother could not cover school fees, gangs extorted the family store, and he was mocked for being gay. “I am physically here, but I’m not really here,” he confided. Within two years, Elder was killed in an attempted robbery. Police dismissed it as a random crime rather than the predictable outcome of gang violence, corruption, and systemic impunity. Fewer than 5% if homicides in Guatemala result in conviction.

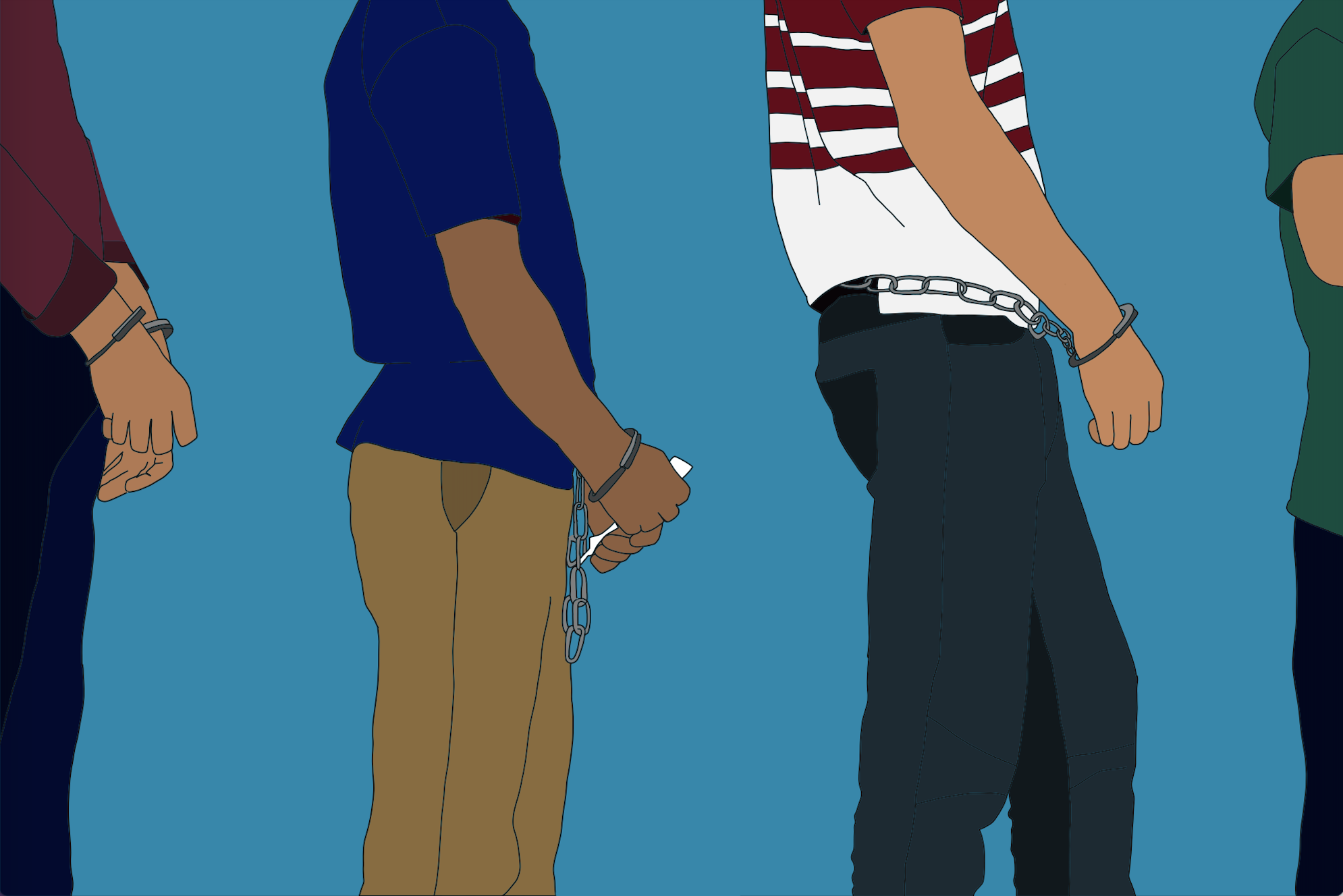

These stories illustrate a broader pattern. In my research with minors returned to Guatemala, 62 percent of deported youths—or their siblings—remigrate. Deportation does not address the conditions that spur migration—whether gang violence, abuse, climate change, poverty, or family separation. It only exacerbates them. While deporting children to Guatemala is not new, bypassing due process and protections under the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act and U.S. immigration law, and executing removals on this scale, is.

This escalation is especially troubling as Guatemala is ill equipped to receive large numbers of children. A 68% reduction of USAID funds to Guatemala gutted the limited state reception infrastructure; one of the country’s two reception shelters has since been shuttered. Follow-up services are virtually nonexistent beyond a handful of community organizations. Politically, President Bernardo Arévalo governs with little power amid entrenched elites known as “the pact of the corrupt,” while Attorney General Consuelo Porras—whom the State Department previously designated as repeatedly obstructing and undermining anti-corruption efforts—remains in office. To assume Guatemala can safely absorb hundreds of deported children is to ignore the country’s political fragility and lack of infrastructure.

Justice Department attorney Drew Ensign insists that Guatemalan children are being “reunified,” not deported. The reality is starkly different. Children remain in Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) custody not because they lack family but because the administration has weaponized sponsorship—sharing ORR and Internal Revenue Service records with Homeland Security intimidates families and turns children into bait. With legal services gutted, children languish in detention.

Judge Sooknanan’s order temporarily grounded the planes. But the deeper question remains: will the United States uphold the protections that children like Camila, Eufemia, and Elder are guaranteed under law, or continue to exploit their vulnerability in the name of deterrence?

Lauren Heidbrink is an anthropologist and author of Migranthood: Youth in a New Era of Deportation (Stanford University Press).