Director of Clinics and Associate Professor of Law, Northern Illinois University

In response to the terrorist attacks in Paris, 34 U.S. governors have issued statements indicating that their states will not accept Syrian refugees. Some intend to put a hold on allowing the government to resettle Syrian refugees within their states until the federal government’s screening process is vetted. These same governors are asking the Senate Majority Leader and the House Speaker to include a provision in the spending bill to prohibit the admission of Syrian refugees.

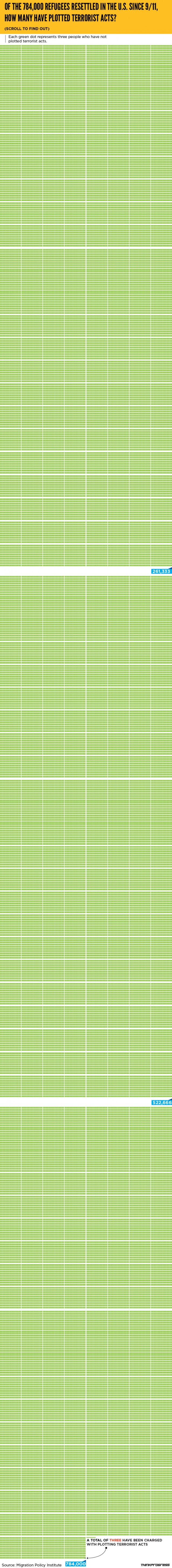

The Paris attacks have also created a platform for presidential candidates to make claims in which they align themselves on the side of safety, national security and a Christian ideology. Jeb Bush recently announced that he would only grant refugee status to Syrian Christians. Mike Huckabee insisted that Paul Ryan should “lead and reject the importation of those fleeing the Middle East” or “step down” if he fails to do so. Reflecting earlier eras of xenophobia and gatekeeping in the U.S., these statements not only misrepresent actual domestic refugee processes, but they additionally ignore the United States’ obligations and commitment to accept refugees under domestic and international law. They likewise perpetuate an inaccurate and violent image of refugees themselves: According to the Migration Policy Institute, of the 784,000 refugees resettled in the United States since 2001, only 3 have been accused of terrorism-related activities, two of whom were not planning attacks in the States and a third whose plans were described as “barely credible.”

Turning away refugees ignores the human face of suffering. More than half of the four million Syrian refugees who have been forced to flee Syria because of violence and terror within their country are women and children. These are people who desire and desperately need safety, security and peace for themselves and their loved ones. The very purpose of refugee law is to provide these things. Should we follow these governors’ actions and turn Syrian refugees away, then we as a nation are ignoring our obligations under both international and domestic law. We are responding to universal human needs with hate and fear rather than compassion.

To understand domestic and international law relating to refugees, some history is required. In 1948, the United States passed Displaced Persons Legislation (1). Under this legislation, the U.S. was to accept only 100,000 persons over a two-year period. Significantly, these individuals had to be registered as displaced on December 22, 1945—effectively excluding those displaced persons, primarily Jews, who entered camps for displaced persons in 1946 and 1947 (Divine 1972: 120 cited in Rodriguez and Legomsky 2015: 906). President Truman and others declared the legislation insufficient, stating that it reflected a restrictionist and anti-Semetic response. In 1950 Congress amended the Act, thereby permitting the admission of more than 400,000 refugees, including those who had been displaced prior to January 1, 1949 (Rodriguez and Legomsky 2015).

In 1950 the United Nations established the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to assist with the resettlement of the one million refugees displaced by the war. A year later, the United Nations adopted the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, which included the international definition of a refugee (2). The U.S. did not sign the 1951 Convention, but became a party to it when it acceded to the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees (3). The 1967 Protocol removed the geographic and time restrictions from the 1951 Convention, which had limited the definition of a refugee to those individuals who were fleeing persecution as a result of WWII.

Despite the United States’ accidence to the 1967 protocol, it did not have an adequate domestic mechanism for accepting refugees. When Congress passed the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, it created a system of preferences, including a seventh preference category for the admission of those who faced persecution and were fleeing either a “communist-dominated country” or a country “within the general area of the Middle East,” as well as anyone “uprooted by catastrophic natural calamity” (Goodwin-Gil and McAdam 2007: 426-427). The annual ceiling for admission under this category was 17,400, a number particularly inadequate to address the growing number of refugees fleeing war and genocide of the 1960s and 70s. Because of the insufficient allowances of the seventh category, the Attorney General frequently used his authority to parole groups of refugees into the United States, even though parole is really a device intended for providing temporary relief (Goodwin-Gil and McAdam 2007).

In 1980 Congress enacted the Refugee Act (4). The Act is significant for three critical reasons. First, it modeled the refugee definition after that provided in the 1951 Convention (amended by the 1967 Protocol). Refugee status thus requires persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion” (5). Second, under the Act the President, after engaging in “appropriate consultation” with Congress, determines the annual admission of refugees. In other words, there are no numerical restrictions. Congress also authorizes the President to allocate additional slots for an “unforeseen emergency refugee situation” occurring after the annual allocation is determined (6). Third, the Act created the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), within the Department of Health and Human Services. ORR is responsible for administrating programs funded by the federal government throughout the U.S. to resettle refugees (7).

The Immigration Act directs the United States Refugee Admissions Program to designate areas of “special humanitarian concern to the United States in accordance with a determination made by the President after appropriate consultation” (8). The current priority system is as follows:

- Priority 1 – Individual cases referred to the program by virtue of their circumstances and apparent need for resettlement;

- Priority 2 – Groups of cases designated as having access to the program by virtue of their circumstances and apparent need for resettlement;

- Priority 3 – Individual cases from designated nationalities granted access for purposes of reunification with family members already in the United States.

Today, there are approximately 19.5 million refugees worldwide, with over 14 million under the mandate of the UNHCR. Fifty-one percent of the world’s refugees are children. In 2014, an average of 42,500 persons were forced to leave their home per day. The term “refugee” encompasses only those who are outside their country of nationality and does not include those who are internally displaced within their country (although the President of the United States can specify special circumstances in which a person could qualify for refugee status if still in her country of origin). For instance, of the 14 million refugees under UNHCR’s mandate, over four million are from Syria. However, there are 7.6 million Syrians internally displaced within Syria who are not designated as refugees.

UNHCR is required to find “durable solutions” for refugees under its mandate. These include:

Source: Syrian child asleep at the Hungary border.

- Repatriation – working with the person’s country of origin to ensure a safe return – an option that has been increasingly unavailable. In 2014, approximately 126,800 refugees repatriated, which is the lowest number since 1983;

- Integration – integrating the individual into the host country;

- Resettlement – an option for those who cannot return home. Approximately 28 nations, including the United States, provide resettlement under UNHCR’s third durable solution option. Importantly, less than one percent of the 14 million refugees are permanently resettled, and the U.S. typically accepts approximately half of those referred for resettlement.

The process of preparing a case for resettlement is long and extensive, and it frequently hinders quick resettlement in emergency situations. Most often, it is the UNHCR who refers a case for resettlement, but it can also be a U.S. embassy or an NGO. There are nine Resettlement Support Centers (RSC) that are funded by the Department of State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration and exist throughout the world to receive and process these cases. RSCs collect biographic and other information necessary for the in-person interviews that the United States Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS) conducts with applicants. Cases are screened by the FBI and put through databases run by the Defense Department and other federal agencies. A person is checked for any grounds of inadmissibility, which would prohibit his or her admission. It is approximately 18-24 months before an individual case is approved for resettlement within the United States.

Under his authority, President Obama allocated admission of 70,000 refugees for fiscal year 2015. This has been the allocated number for the past few years, but it’s important to note that in the past the number was much higher. For instance, in fiscal year 1995 112,000 refugee admissions were authorized, and in 1991, the number was 132,000 (Rodriguez and Legomsky 2015: 912). After the Vietnam War, 402,000 Vietnamese refugees were admitted. At the same time, the number the President authorizes does not necessarily result in that number of refugees being admitted. For example, 70,000 admissions were authorized for fiscal year 2002, but, as a response to 9/11 only 18,652 were admitted. In 2003, 50,000 were authorized for admission, but only 25,329 were admitted. Rodriguez and Legomsky 2015: 913.

Of the 70,000 refugees admitted into the United States during the 2014 fiscal year, only 249 were from Syria. Since September 2015, the U.S. has accepted 1,854 Syrian refugees. In accordance with the Immigration and Nationality Act, President Obama announced that he would increase the 2015 allocation by 10,000, an amount that would derive from the 18,000 referrals submitted by the UNHCR. More than half of these referrals are children.

The restrictionist response to the Syrian refugee crisis is strikingly similar to the U.S.’ response toward Jewish refugees during World War II. In July 1938, 67% of Americans opposed admitting refugees. In January 1939, Americans were polled and asked whether the government should permit bringing in 10,000 children – mostly Jewish – to the United States. Sixty-one percent said no. In the spring of 1939, the Nazis allowed the SS St. Louis, a ship carrying European Jewish refugees, to leave Hamburg for Cuba. Nazis arranged to have corrupt Cuban officials deny their entry, even though they were granted visas. After being turned away from Cuba, the United States denied the ship’s entry as with President Roosevelt’s announcement that the U.S. was unable to accept more refugees because of immigration quotas. The ship eventually landed in Holland, and Great Britain, Holland, Belgium and France accepted the refugees. Ultimately, however, over 600 of the 937 passengers on that ship were eventually killed by the Nazis. In retelling this story, Professor Bill Ong Hing (2000: 590-591), notes “When the United States refused the S. Louis permission to land, many Americans were embarrassed; when the country discovered after the war what happened to the refugees, there was shame.”

Today, ISIS has forced millions of people to flee their homelands to escape its terror. Just as many of the Jewish refugees perished, so too might many of the refugees America now seeks to reject. This has many humanitarian consequences, but it also has security ones, as well – a fact ignored by political pronouncements favoring the refusal of refugees. “The alternative now to an open-door policy is to leave the Syrian refugees and their children festering in Middle Eastern camps, creating the radical armies of the future.” This does not make me feel safer. In fact, it makes me feel shame.

I am reminded of the words of Palestinian-American poet Naomi Shihab Nye who calls us to transform human suffering, not into more fear and oppression, but into kindness:

“Before you know kindness as the deepest thing inside,

you must know sorrow as the other deepest thing.

You must wake up with sorrow.

You must speak to it till your voice

catches the thread of all sorrows

and you see the size of the cloth.

Then it is only kindness that makes sense anymore,

only kindness that ties your shoes

and sends you out into the day to gaze at bread,

only kindness that raises its head

from the crowd of the world to say

It is I you have been looking for,

and then goes with you everywhere

like a shadow or a friend.”

I call on all U.S. governors and their constituents to learn from history, to resist fear, and to transform the suffering of Syrian refugees into a life of hope in America.

Citations

1. Act of June 25, 1948, Ch. 647, 62 Stat. 1009.

2. 189 U.N.T.S. 137.

3. 606 U.N.T.S. 267, 19 U.S.T. 6223, T.I.A.S. No. 6577.

4. Pub.L. 96-212, 94 Stat. 102 (March 17, 1980).

5. INA Section 101(a)(42).

6. INA Section 207.

7. See also INA Section 411.

8. INA Section 207(a)(3).

Works Cited

Divine, R. A. (1972). American immigration policy, 1924-1952 (Vol. 66). Perseus Books.

Guy S. Goodwin-Gill & Jane McAdam (2007). The Refugee in International Law (3d ed.): 426-27.

Hing, Bill Ong. "No Place for Angels: In Reaction to Kevin Johnson." University of Illinois Law Review (2000): 559.

Rodriguez and Legomsky. 2015. Immigration and Refugee Law and Policy, (6th ed).

Anita Ortiz Maddali is the Director of Clinics and Associate Professor of Law at the Northern Illinois University College of Law. She writes about and teaches immigration law. Prior to coming to NIU, she represented women and children who were fleeing violence and seeking asylum in the United States. She is a graduate of Northwestern University School of Law.