By Cora Siré

Before experiencing the Nasher Installation, what did I know about Syria?

Words and images derived from headlines on a country imploding before our distant eyes. Aleppo attacked, Homs destroyed, Damascus under siege. Journalists write of food shortages, power outages, checkpoints, armed militia, and chemical warfare. Photographs depict children on stretchers, rubbled streets and refugee camps. The news feed is nonstop, the facts abstract and hard to process. Millions affected by death, injury and displacement caused by the violence of Syria today.

An installation by Dima Karout changes my perceptions. During her solo exhibition at Montréal Arts Interculturels (MAI) in 2014, I encounter a stunning visual and textual interpretation of the Syrian experience that transcends statistics and facts. An artist and writer from Damascus, Karout studied in Paris and was living in Montréal at the time, before relocating to London.

Who are you after you lose your home?

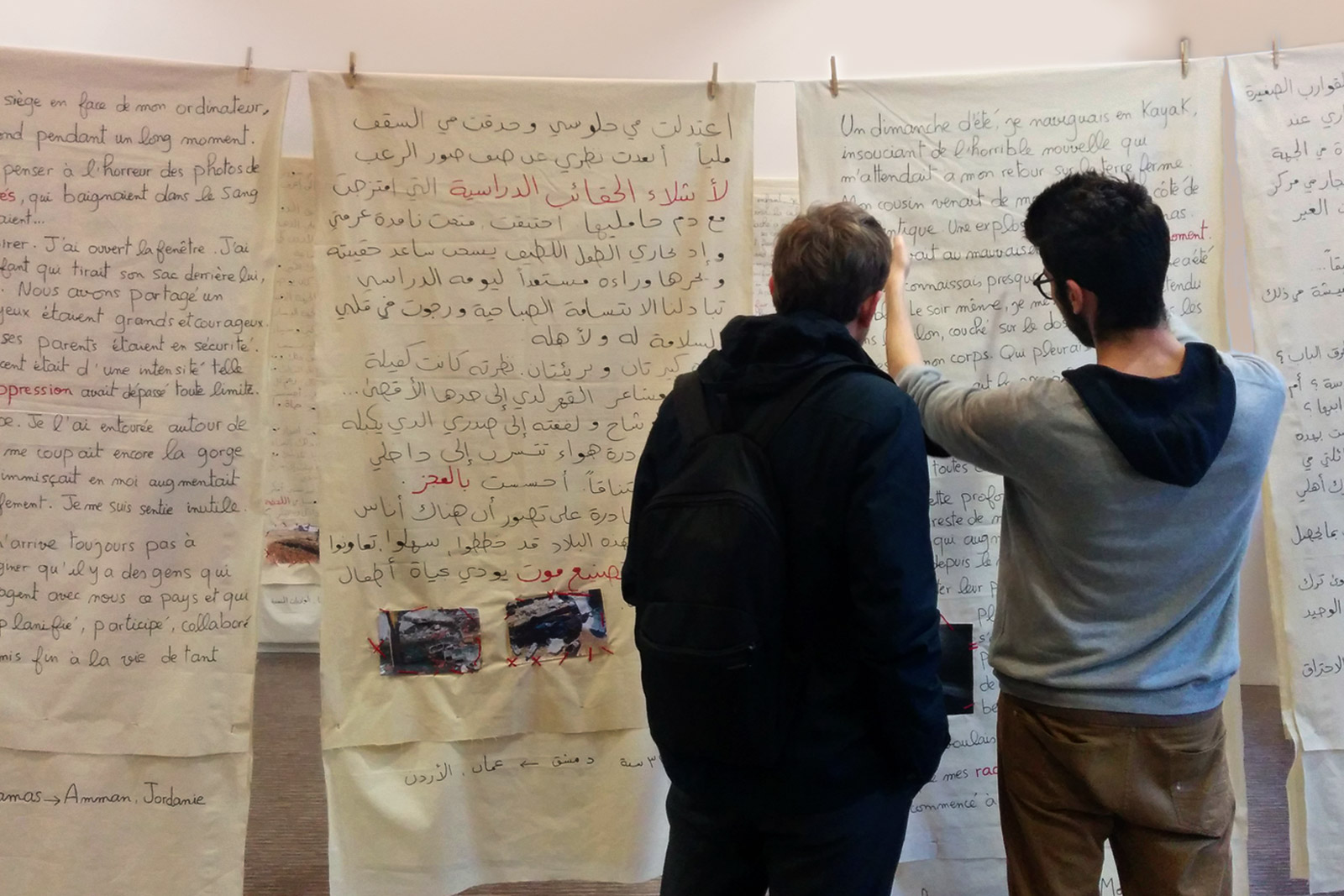

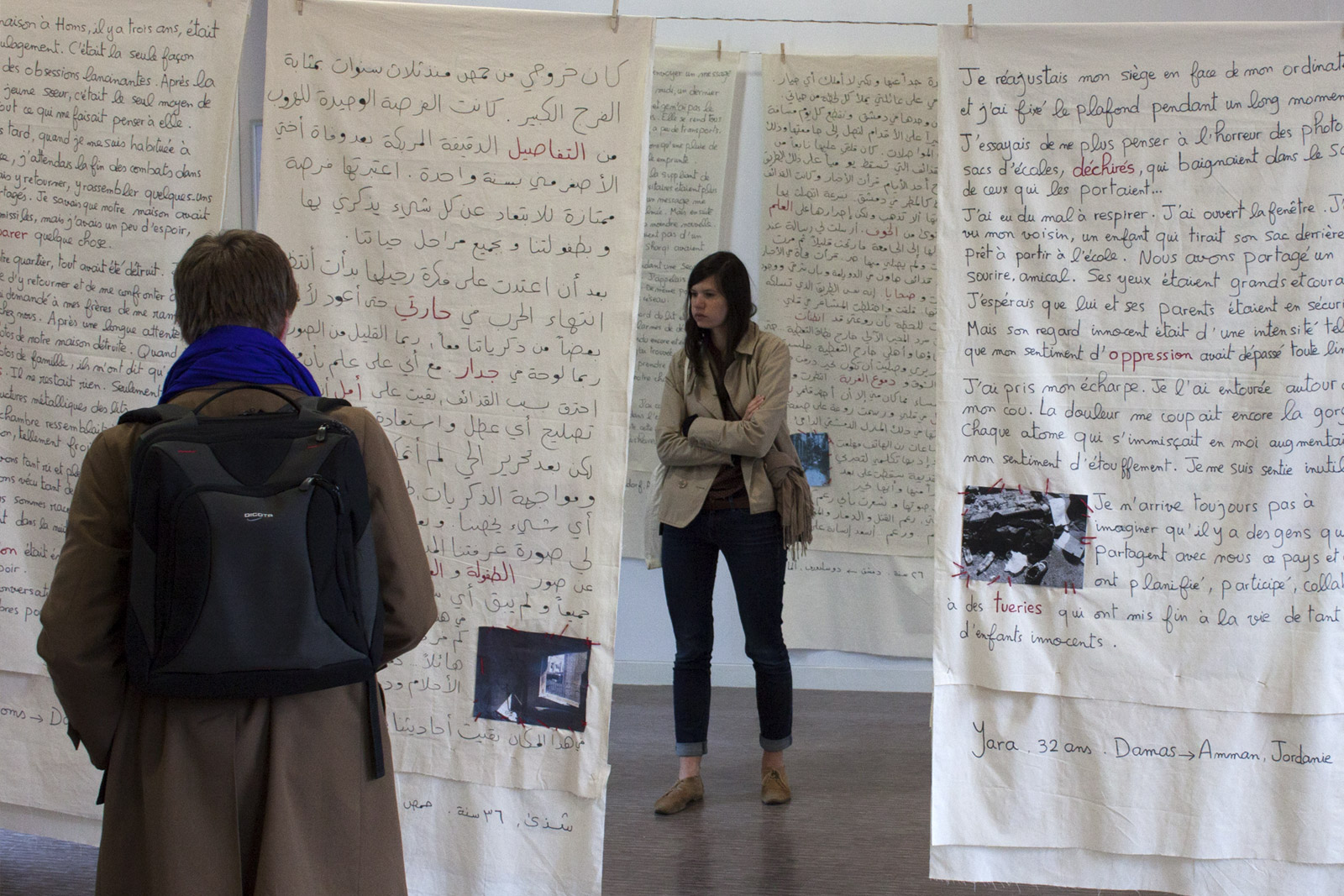

The gallery in MAI is cavernous, but Karout’s clever use of space gives viewers the sense of a personal encounter and the privacy of a journey to confront the direct experience of war and exile.

It begins with a montage of texts and photographs of Old Damascus walls. The artist introduces two unnamed characters – ‘She,’ a Syrian traveller, and ‘He,’ a Syrian refugee. Presented separately, each of the characters comes to life as Karout delves deeply in exploring their internal conflicts and the walls, or isolation, of their shattered identities. ‘She’ left before the conflict and her memories of Syria are vibrant and colourful. ‘He’ left during the conflict and his are bloody and grey. Both are haunted by survivor guilt as they process the ongoing death and destruction in their former country. Where they meet, metaphorically, is in exile, trying to find answers to the artist’s searing question, “Who are you after you lose your home?”

Dreams summarized in a few drops of water.

In addition to the fraught circumstance of exile, the roles of memory and imagination in overcoming loss are expressed in the Nasher Installation, a collaborative feature of Karout’s exhibition and her most impressive achievement.

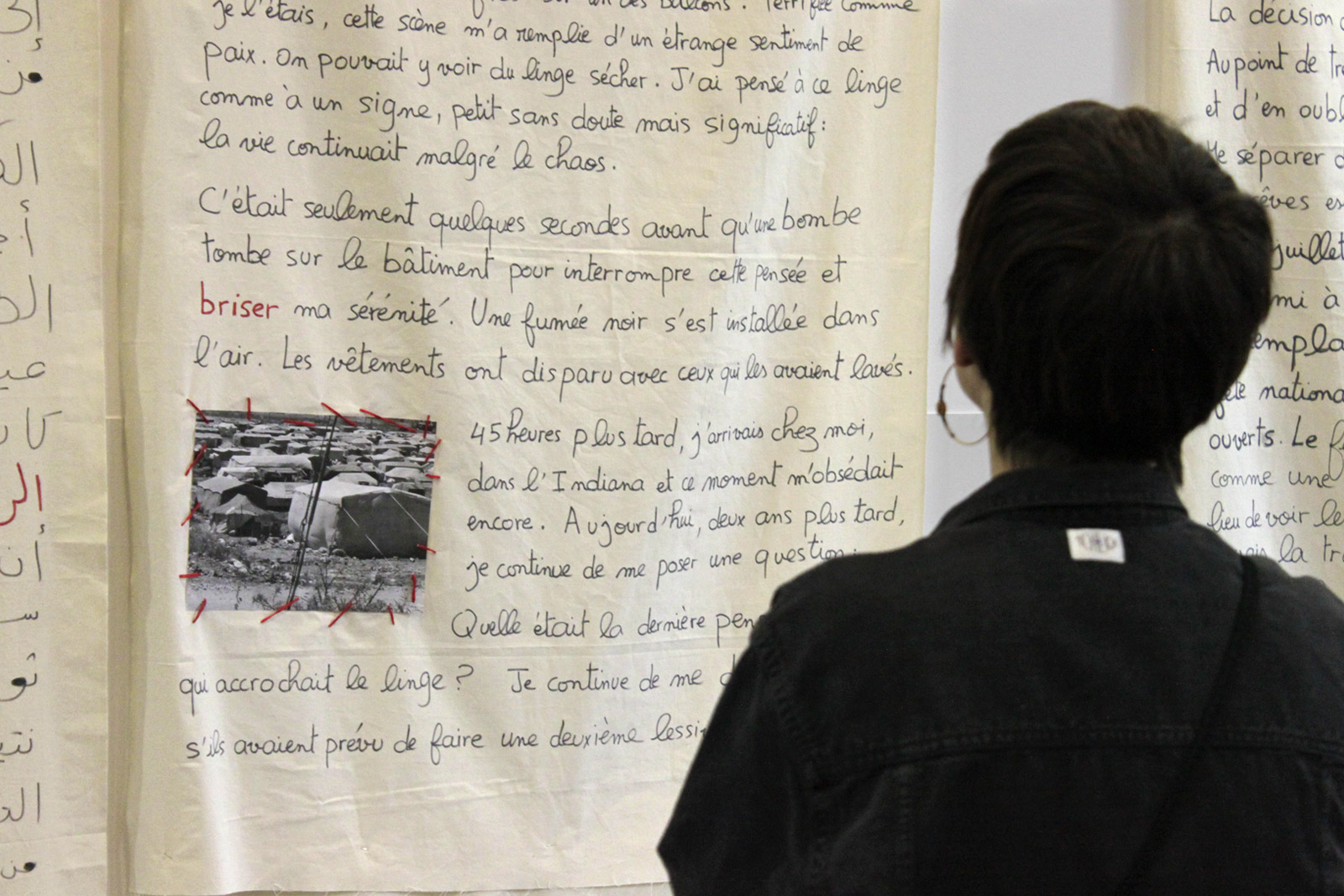

Two rows of massive canvas-like fabrics hang in pairs, like laundry, from wires suspended in the gallery’s high ceiling. Each canvas tells a story hand-written in beautiful script – black and occasionally red lettering – presented in Arabic and English. Here I pause to read verbatim excerpts of the many stories the artist collected from a diverse group of Syrians, some in exile, others not, including women and men, many young.

The visual effect is that of textile art. The fabric comes alive as it wafts to the air circulating in the gallery. The amplified size of the canvases conveys the magnitude of individual suffering and resilience in stories told by witnesses from their varying points of view.

On the canvasses, I read firsthand accounts by Syrians such as Jean who remained in Aleppo. He tells of the impact of the conflict on the city’s children. Before the war, they played carefree in the parks and streets. Now they are obliged to collect water in containers for their families which the children do with pride and touching dedication, struggling to carry the jugs and bottles home. “All their dreams summarized in a few drops of water!”

Another canvas tells of Ibrahim’s struggle to adjust to his new life in Paris. He sees the Eiffel Tower as his wall of suffering but yearns to find something positive in this symbol. “It is a metal wall with plenty of voids ... maybe there is a glimpse of hope.”

The best way to reach peace is art.

The personal accounts bear witness to the consequences of the war, transcending political or religious affiliations. Sawsan describes having to leave Damascus after a massive explosion. Now in Beirut, she misses her workshop, her tools and the inspiration her former city always brought her. As to the way forward, Sawsan affirms, “The best way to reach peace is art.”

Karout’s installation juxtaposes two meanings of the Arabic word, Nasher. It refers to both the act of hanging clothes outside to dry and the publication of words, texts, or statements.

The account by Soulaf integrates both meanings as she recalls a scene from Damascus. While driving through the city by car during heavy bombing and sniper attacks, she sees laundry hanging outside a third floor balcony. “Terrified as I was, that scene filled me with the strangest sense of peace.” Another bomb explodes and “the laundry disappeared along with the ones who washed it.” After she returns to her home in Indiana, the scene haunts her – not the erasure caused by the bombing so much as the questions of who had washed the laundry and whether they’d planned a second load.

Speaking over the facts of the conflict in Syria, Nasher gives voice to its impact on the human family. Karout’s installation does not sag in sadness but soars with authenticity and visual ingenuity. After many hours, I leave the gallery feeling I’ve discovered truth in all its complexity, not abstract but heart-achingly real.

Cora Siré is the author of two novels, Behold Things Beautiful and The Other Oscar, and a collection of poetry, Signs of Subversive Innocents. Her essays, short stories and poetry have appeared in anthologies and literary magazines in Canada and Mexico.