By Sarah Walker

Counter-narratives from young African men who sought asylum in Italy as children reveal how they contest the victimising ‘unaccompanied minor’ label. As Sarah Walker demonstrates, it is a label constituted through colonial and racial logics.

Amadou, a young Gambian who sought asylum in Italy as a hopeful sixteen-year old, has always drawn. I first met him in 2018 during ethnographic fieldwork in ‘Giallo’, a reception centre for unaccompanied male minors in Verde, a Northern Italian city, where he was then living. The fieldwork was part of my doctoral research where I studied the transitions to adulthood of young African men who made the perilous illegalised journey to Italy via Libya across the Mediterranean Sea. These are young men who, upon arrival in Italy, are not only transformed into ‘unaccompanied minors’, but who must also confront Italian constructions of Blackness. My research explores how art can function as an entry point to different life worlds (for details see Walker, 2019). This methodology also recognises how trauma can be difficult, if not impossible, to put into words.

Because of its geopolitical position as border of Europe and its complex racial landscape, Italy is a particularly compelling fieldwork site. In theory, though rarely in practice, Italy also offers young migrants a greater level of protection than other EU Member states via its provision of post-eighteen support. Under Law 47/2017 (the Zampa Law), unaccompanied minors are granted access to ongoing accommodation, training and a support worker beyond childhood. This challenges the ambivalent moral temporality of the EU’s socio-legal landscape, in which the unaccompanied child is temporarily entitled to conditional hospitality until the threshold into adulthood is crossed (Walker and Gunaratnam, 2021).

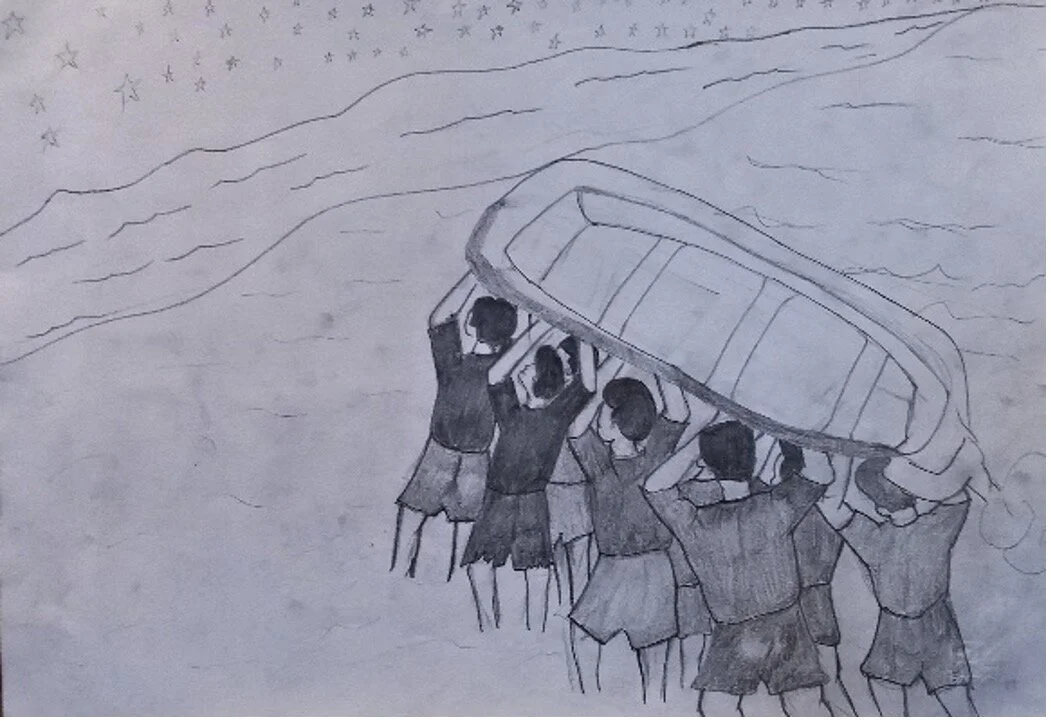

Amadou shares many drawings with me as part of my research, including the below, depicting young men carrying a boat to the sea in Libya. He explains:

‘It was night, this represents the storm, and this is us… holding the boat […] This is the perfect picture of … illegal immigrants [laughs]. So, they use us in everything. We carry the boat. With the machines and everything fixed. So heavy, so difficult. You have to drag it to the sea.’

Figure 1. ‘The perfect picture,’ Amadou

The picture is perfect in how it depicts the use and abuse of the racialised body – ‘they use us in everything’. The Black body has no value, save as labour; it is otherwise disposable. Amadou’s drawing can be understood through its reflection on the use of the Black (migrant) body in its own labour. It captures more than the helpless victims on the boats, an image so often portrayed in the media. Here, photos are usually taken from above and show packed (Black) bodies in overcrowded vessels bobbing helplessly in the sea. Instead, Amadou’s drawing reverses this image, showing the agency and complicity of those about to embark on the journey, as well as the way in which they are ‘used’ at every stage. The small boat, too small for so many people, held over their heads, at once a talisman of hope and a weight and burden.

This is also a visual representation of the politics of abandonment and European border controls, as a result of which the sea ‘has been made to kill’ (Heller and Pezzani, 2017). This is compellingly shown by Forensic Oceanography’s ‘Left-to-die boat’ . And yet people continue to embark on this journey more than once, knowing full well the risks that await (Rigo, 2018). It is risk-taking that reflects the geographies of violence and death stretching throughout migration trajectories. Yet, it also reflects the hope for a life ‘like everybody’ has, as Edrisa, a young Gambian, puts it. Put differently, it is what Kohli has called ‘thick’ stories, an expression of an ordinary wish to succeed in life. For young men like Edrisa and Amadou, the only way they come to see this ordinary wish being achieved is to risk death on a rickety boat across the Mediterranean Sea.

Adama, another young Gambian, tells me they ‘take the back way because Europe has closed the front door…’. In recognising ‘these are the routes that were made by Europe from Africa for the slaves’, Adama historicises his own movement, but does not quite capture the whole. In the past, the Mediterranean was traversed in the opposite direction by Italians. In Libya—an Italian colony from 1910-1947—some 13% of the population was made up of Italians in the 1930s (Chambers, 2017). Indeed, Italians themselves have occupied positions of subalternity in relation to constructs of whiteness and European imaginaries. Luigi D’Alife’s recent film The Milky Way highlights how the trajectories of today’s migrants seeking to cross the French border over the Alps are the very same as those made by Italians illegally crossing to France in search of work in the past.

Indeed, people have always moved. The 17th and 18th century sawvast movements across the globe , including children, as a result of Empire building, slavery and colonialism (Fass, 2005). Today's migration flows often follow the trade and social pathways established during that period. Yet it is only today that in Europe ‘migration’ has come to signify problematic mobility, implying the need for control (Anderson, 2013). Rather than mobility, the figure of the migrant relates more to race, gender, class and nationality. It is a construct that is inherently racialized, deriving from migration regimes based upon historical colonial frames of reference and cultural norms.

These young men’s counternarratives reveal themselves to be more complex political subjects than the vulnerabilising label ‘unaccompanied minor’ suggests. Aware of their postcolonial position of marginality, they seek to contest this through the rights they maintain they are entitled to, including the right to mobility. Inverting the Eurocentric lens draws connections between human mobilities across time and space and serves to normalise mobility rather than construe it as a ‘problematic’ threat.

Viewing the movement of people through a historical lens shows how migration is simply a part of human life. It similarly illuminates the unjust and immoral border controls that enhance migrant vulnerability and exposure to harm, even death. Migration can be considered ‘an act not only of survival but of imagination’. Migration can be understood as a tactic of creating futures, of maintaining hope. It is simply that this hope for some young people is not accessible via legal channels, rendering some lives more disposable than others.

About the author

Sarah Walker has worked as a social justice researcher and a practitioner on migration for over a decade. Her research is inherently interdisciplinary, focusing upon borders, migration, gender, race, and coloniality. Currently, she is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Bologna, Italy, working on the ClimateOfChange project which examines the nexus between climate change and migration. This blog piece is based upon research conducted as part of her ESRC funded PhD in Sociology at Goldsmiths, University of London, and discussed in Walker and Gunaratnam (2021) . You can follow her on twitter at @stowsarah.