(Español abajo)

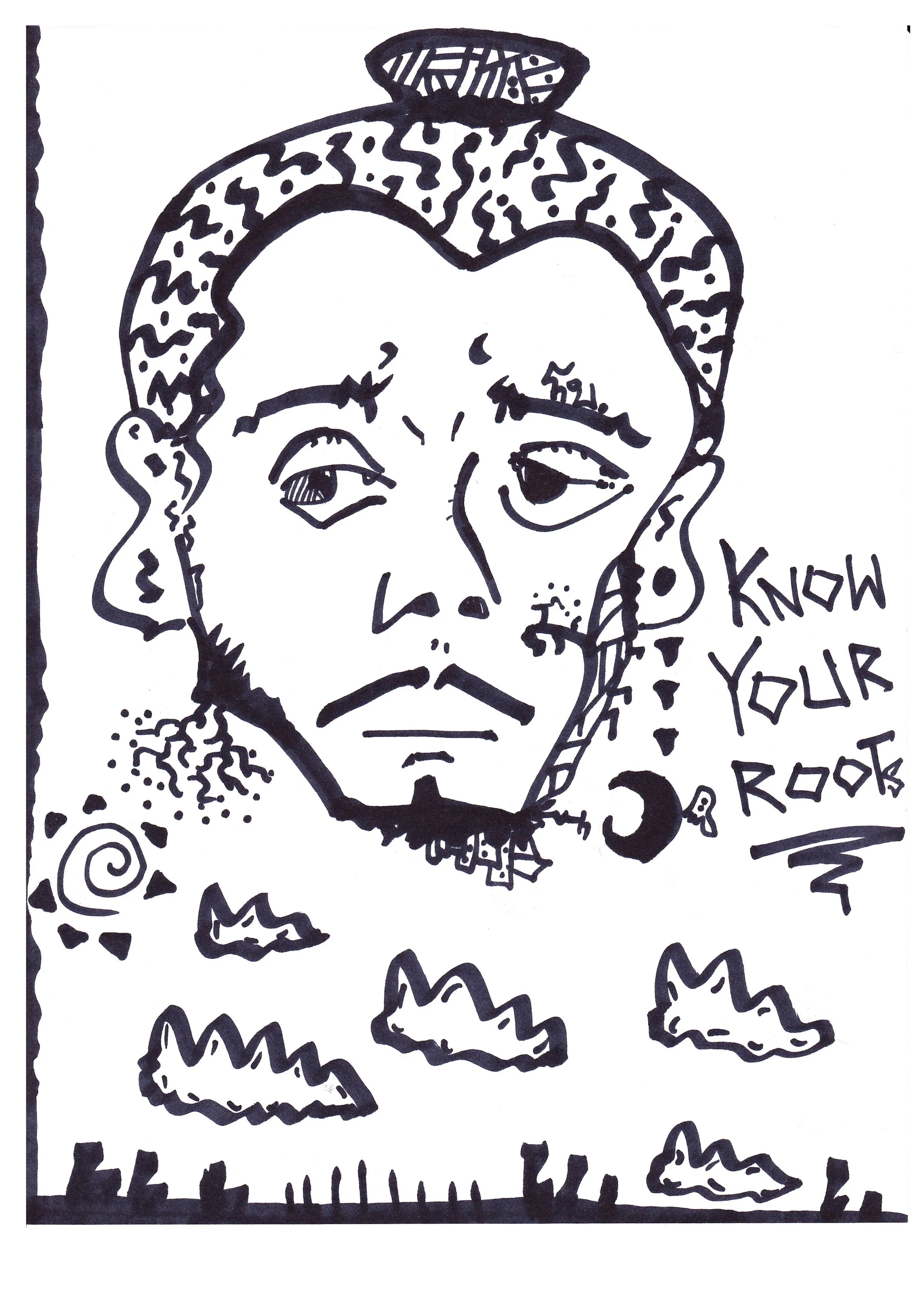

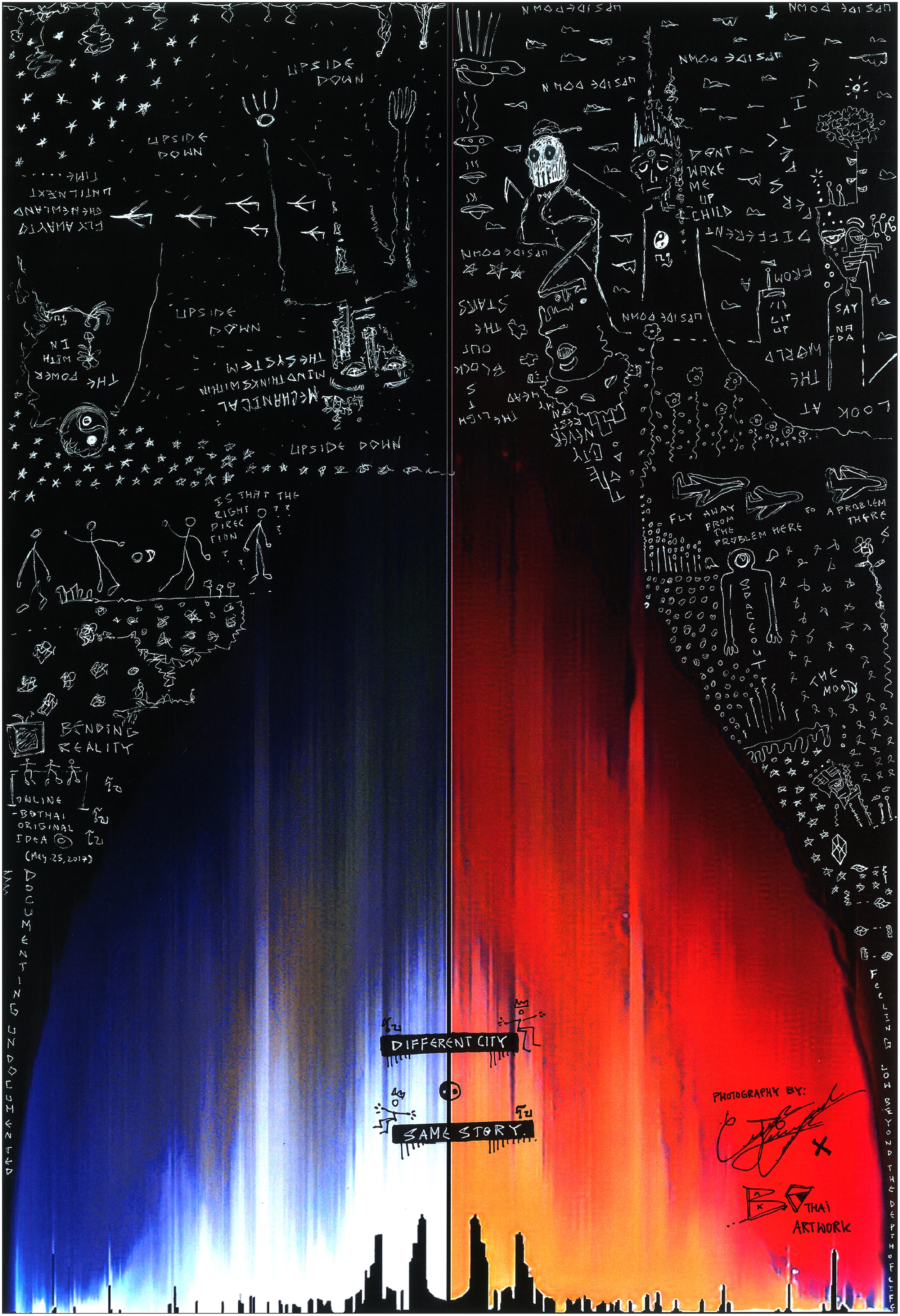

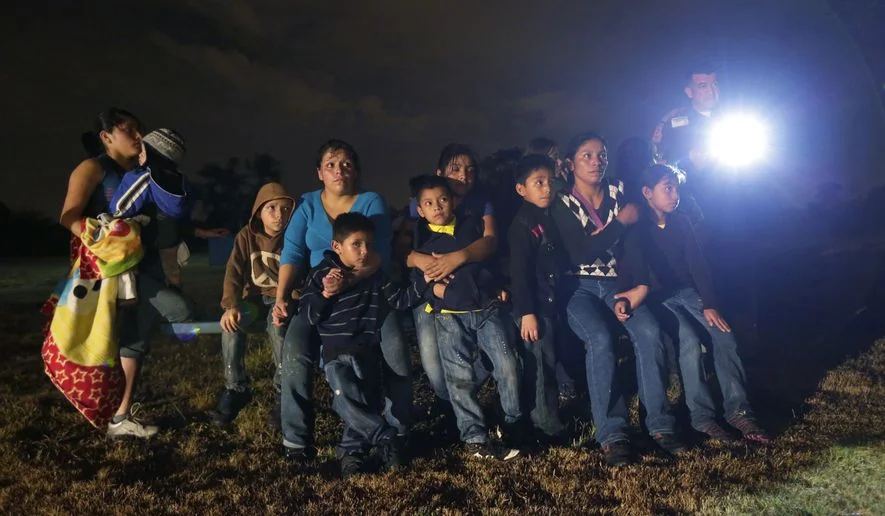

In the first of this two-part series, the Linea 84 Collective employs ethnographic journalism along the Mexico-Guatemala border to reveal the intricate stories of young Central Americans running away from their home countries, becoming part of the flow of undocumented immigrants and therefore a target of increasingly militarized security policies in the North and Central American region.

Specifically, in the regions of Tabasco (Mexico) and El Petén (Guatemala), state protection is scarce and repressive actions are abundant. Both shape the everyday life of CentralAmerican youth fleeing to the north. Drawing from research in migrant shelters, along train tracks, and in various local towns, we enlist ethnographic journalism to move beyond reporting events to focusing on the ways young people make meanings of these everyday events and their impacts on social life.

In what follows, the authors complicate common representations of migration by deftly weaving together the overwhelming presence of death, the experience of deceit, suspicion, mistrust and loneliness with visceral moments of conversation and music, thus showing the ultimate uncertainty of the migrant trail. “La vida corta” tells the story of “Black”, a young Honduran migrant who travelled periodically from his home country to Monterrey (in Northern Mexico) crossing territories controlled by organized crime, unreliable authorities and mistrustful locals until one day he disappeared without a trace. In “Everything is for Sale Here” we see howWilson, a 13 year old asylum seeker, is abused in the country he is asking for protection by older men, some of whom present themselves as merciful individuals ready to help young migrants in need.

LA VIDA CORTA*

Close to the water treatment pipes, where migrants bathe in Rio Usumascinta, Tenosique, Tabasco. Photo by: Irving Mongradón

I was supposed to meet up with Black, but he didn’t show up at our meeting spot. I went to look for him again the following week. Nothing. I looked for him everywhere. I had met him a month earlier, and we met regularly. He always showed. I went back to “Golden Dreams” – a little town on the side of the road from El Ceibo, very close to the Guatemala border. I waited for five hours. Boys on motorbikes turned their heads to look at me. They knew I was looking for Black. I think they pitied me. The heat was intense, and I couldn’t stop sweating. Each time I turned to look at them, the look on my face made it clear that I wasn’t going to move. They started speaking amongst themselves and, finally, one of them put on his helmet, got on his motorbike, started the engine loudly, and stopped right in front of me. He just stared at me.

“I’m looking for Black.”

“No,” he told me with a shake of his head.

“When is he coming?” I asked. He shook his head no again. He took off his helmet, and then I saw it in his eyes. “He never made it to Monterrey,” he told me. He started the engine and left.

This trail that migrants take northward is very long. The trail devours them. It extends beyond the borders with seemingly no end. People who walk this trail are already taken for dead.

I left “Golden Dreams.” I never saw Black again. I’m certain he’s dead.

* The title is a word play of “la vida loca” (the crazy life) which is a common saying among gang members used to describe their hectic lifestyle.

BLACK

Near the railroad tracks in Tenosique, Tabasco. Photo by: Irving Mondragón

“What’s your name?”

I ask a boy with bee-like eyes who was listening to la Santa Grifa— a hip-hop band— on his phone.

“Well, fuck” I thought. Here we are in the southern border of Mexico, this guy is Central American, and this hip-hop group is from Tamaulipas. It piqued my curiosity. Tamaulipas is very far away, it’s a border state in the north of Mexico with more than 4000 firearm deaths in the last 7 years. This state also has a role in everything that has to do with immigration; it is one of the most dangerous border crossing points for those headed to the United States. La Santa Grifa know how to talk about all this violence, even though they don’t rap directly about coyotes, shelters, or migrants.

The boy utters some name while looking side to side to observe the people’s comings and goings. He wears a backwards baseball cap, dark pants, and a light shirt. I sit next to him on the low wall around the dining hall of aCatholic shelter that receives people who are in transit through Mexico. The majority of these places work to defend migrants’ human rights. They provide a combination of humanitarian assistance and human rights attorneys who help migrants seek asylum. And for better or worse, these actions have earned the Catholic church power and prestige among organizations and institutions that deal with migrant defense issues. The Church combines faith and law to get in the game.

“Where are you headed?” I ask.

“Monterrey,” he answers shortly.

His answer surprises me. Monterrey is in the border state of Nuevo León, not that far away from the border with the United States. A lot of people passthrough this city, waiting for a few days, sometimes weeks, before heading to the border towns like Piedras Negras, Reynosa, or Nuevo Laredo where they wait until the border “opens” and “make the jump” to the other side. To be clear, they wait in line with drugs and weapons until it is their turn to pass.

But the boy doesn’t tell me he’s going to the United States.

“And why are you going there?” I inquire.

“I work there and then I come back down to see my jaina (chick) and my family in Honduras.”

In recent years, Mexico has become a destination for many Central Americans. They establish themselves here not because Mexico is the land of plenty but because people seek to escape the chaos governing their countries. Some get stuck in Mexico. Others disappear. The authorities persecute them. They beat them. At the end of the day, whether by choice or force, Mexican authorities are part of the criminal business, holding migrants indefinitely in detention centers as they wait for justice to arrive. But justice never arrives, only bureaucratic, institutional, formal, sterilized state violence. The Mexican and Central American governments inflict violence without pity nor remorse—all at the behest of U.S. securitization policies. Funded by the U.S. State Department and trained by U.S. Border Patrol Tactical Unit, elite military units in Central America seek to curb outmigration. Rather than attend to the needs of families and communities, in practice, these special military-police and anti-gang units inflict violence upon migrants.

Many Central Americans have been able to establish themselves inMonterrey, a prosperous city in northern Mexico. To make it to this city means that one has to know how to move across Mexico.

“So, you work there, you come and go. But it’s very dangerous going through these paths, going up and down. This is no-man’s-land,” I tell him.

“Yep. A lot of Zetas in Veracruz,” he shrugged.

In addition to Tamaulipas, Veracruz is one of the riskiest states for those headed north. It is a bastion of the Zetas who control parts of the south and northeast Mexico. The Zetas emerged from the former armed wing of the Gulf Cartel, when Osiel Cárdenas Guillén was their leader. They are an armed group who initially was at the service of a cartel which was composed of deserters from the elite Mexican army unit known as the GAFE (Grupo Aeromóvil de Fuerzas Especiales), many of which were trained by the U.S. military. Now they serve only themselves. After the capture of Cárdenas, the Zetas became mercenaries. With neither the leadership nor the contacts to become a drug cartel, the Zetas had something much more valuable; the knowledge and ability to exact violence efficiently in order to control all other lucrative illicit industries. With their capacity for destruction, they controlled criminal networks in the Gulf Cartel’s territory. They co-opted human smuggling.

To gain control of human smuggling in Mexico, the Zetas started threatening coyotes, guides, recruiters, and entire communities that lived off of the passage of people. They forced them to become their allies and pay them taxes… to become their employees. Any resistors were killed. Migrants became the spoils of war. Mass kidnappings, like that of the San Fernando massacre, began in earnest at the end of 2008.

“But look,” he tells me, “I already know my way around here like the palm of my hand. I go through ‘Golden Dreams’ and I arrive here. I run, I move quickly, nimbly, and like I tell those who come with me…” Black glances at a trio of young men whose eyes are heavy from marijuana and continues, “If they can keep up, they follow me. If not…”

People walk by and he stops talking. He’s prudent. He knows that here, everyone hears everything. “I’ve got a pound of weed with me, do you understand? I’m just passing through here and I’ll be on my way.”

“I understand you. I’m sure you smoke all that by yourself, right?” The ice breaks and we start talking about la Santa Garifa. Black became a member of the Mara Salvatrucha when he was 13 years old, but not a member who is sympathetic to them or who dreams of being part of a gang, no. He was trained. You can see it when he speaks, and how he acts. He’s got street, insider wisdom (clecha). But he’s not a boss.

When I ask him why he left Honduras, he tells me dryly:

“Look. Here’s how it is. I lived with my jaina (chick). I went into an 18 (gang) territory to sell drugs and mess around with a girl there. I didn’t ask for permission to sell and she was the girl of a member of the 18. You can’t do that. When I go back to Honduras,I put on makeup, a skirt, a wig and that’s how I can go visit my family and my girl. I can’t be there for very long. So I head back up and I bring with me something to sell and be able to endure the route.”

Who knows if this is the whole story? We never finish talking. All I know for sure is that he knows how to get to Monterrey from Honduras, with all its dangers.

“Have you thought about staying here in Mexico?” I ask him. His beady eyes look around. He hasn’t yet started to speak when someone moves next to us.The conversation stops dead. He turns to look at me and says, in a low voice,“We can’t talk here.”

We agree to meet up in a week in “Golden Dreams” at the edge of the highway, where other young men like him gather with their motorbikes.

“So who do I ask for?”

He looks at me. He fixes his gaze.

“They call me Black.”

He turns and leaves. I watch him as he walks away. He has the letter “B”embroidered on that backwards cap.

AT GOLDEN DREAMS

Train tracks at Salto de Agua, Mexico. Near the border with Guatemala.Photo Credit: Irvin Mondragón

One week later I’m standing in Golden Dreams. It is a small town close to the Guatemalan border. According to official statistics, its population is about 300. It is a forgotten little town at the edge of the border. There is nothing in this place except it is part of the trail migrants take.

After waiting for three hours, I think that Black isn’t going to arrive. Then he appears, seated on the back of a motorbike with one of the kids who gather on the edge of the highway. This is where I get to know Black, and where I begin to understand a part of the world where adolescents fleeing the violence in Honduras live.

Since he was 11 years old, Black has seen dead bodies. His neighborhood, one of the poorest, is considered one of the “hottest” in San Pedro Sula. He describes days of “slaughter” that have not ended yet. People are terrified to leave their home because they are surrounded by death. In a single day, there could be “one dead body on the corner, another in front, just up from the store, on the other street, and so people live in the midst of dead bodies.” At first, Black asked about so many murders, but he quickly learned that it was better not to ask. Cadavers formed part of his daily life. That’s how he started to ignore death and to live with the end of life every day. Later, he became a member of theMS-13 (Mara Salvatrucha). He describes his history casually. For Black, to be a marero is not that different from seeing dead bodies from the sidelines. Becoming a marero is part of the same situation: poverty, inequality, anti-gang operations, death squads, and unstoppable migration of youth. It is simultaneously overwhelming and banal.

By becoming a gang member, subject to torture and disappearance by the police or the military, he became no one to the Honduran state. But if we are frank, Black, who never told me his real name, was never really anyone to the Honduran government. People like him are no one to us. Dismissing him as a gang member allows us and the government to rationalize that he deserves the worst kind of death. It allows us to sleep calmly at night. Let’s not deceive ourselves. Now he is someone, but someone who deserves to die at the hands of whoever, wherever. It doesn’t matter.

Black “had to distance himself” from the gang and was thereby banished him from his country. He had to flee, so he crossed through Guatemala and went north. He started working in Monterrey at odd jobs to earn a few pennies, party, eat, and occasionally return, dressed as a girl for safety, to Honduras for a few days. His life was this route—back and forth to the north and to the south. The doors closed in every country. He could not stay in Honduras; the government there would not protect him. To Mexico, he was a headache. The United States wasn’t even a consideration. So he risked his life and kept moving. He sold a little bit of weed to travel to Monterrey – and once there, he smoked the rest himself.

He knew people along the whole route, the majority of whom were young guys like him – some Mexican, others Hondurans, Guatemalans, Salvadorans. Many of them panhandled along the train tracks or in the streets of the passing towns. Black didn’t like to beg, so he didn’t panhandle. The boy with the beady eyes knew life along the train tracks, starting in Tenosique. He knew how young men like him survived.

We saw each other a few times in this town and talked in the oppressive heat. “Here, there are rules,” he said. He told me that those who more or less control what happens along the rails are those with food stands, or those who rent rooms to Central Americans. There’s Don Pepe, a Honduran of about 40-50years old who has a Cuban accent because he lived for many years in Miami. He always looks out from his stand at those who arrive. Above all, the women. He sizes up new arrivals and doesn’t let them start fights near his place. Don Pepe’s catch phrase is “Here, we are going to behave ourselves.” He offers rooms for rent and sells Honduran food. He doesn’t hesitate to take out a stick and break it over the head of anyone who bothers his clientele or who causes disturbances. He also doesn’t hesitate to call immigration.

In front of the station, Don Goyo rents dirty rooms and sells fruits, vegetables, beer and probably drugs to nationals and foreigners alike. Who knows who he’s affiliated with, but things have gone well for Don Goyo. He has a son who is an astute scoundrel. His son is Don Goyo’s eyes and ears on the streets. Together, they ensure new arrivals don’t cause any problems, at least not near their business. Black says Don Goyo and Don Pepe know all of the groups that assault, rape, and kill; that’s business in these parts. They let the youth panhandle and walk around there, but they don’t like homeless people from any country and they don’t want trouble.

The boy with the penetrating stare knew many boys in this place. You start to recognize the young guys who are always walking through. One time I asked him how else they made a living, besides panhandling. “You’ll see,” he told me.

Before he disappeared, Black introduced me to Wilson. The first day I met Wilson, he walked up to us and Black immediately began heckling him, shaking with laughter and calling, “Hey you, and how’s Don Simón? Ha ha.” It was clear that Black was making fun of him. Wilson laughed, but he looked away with shame. Wilson’s right eyelid almost always covered half of his eye. It seemed like he was high but that was just his facial structure.

“Wilson goes to an old jerk’s house who lives along the train tracks,”said Black. “Don Simón likes the young ones like Wilson.”

This Don Simón operates like this: The boys go by panhandling and then Don Simón offers them soda, a bag of chips, and has them do odd jobs – move rocks from one side to another – the most useless things in the world. He gives them money, then he lends them the computer, so they can connect to Facebook. Then he starts to touch them.

“Here in this place. Like this, look!” Black says while he gathers his fingers together, indicating a whole lot. “There’s a ton of jerks like this Don who look for young boys like Wilson. Because Wilson gives it to them in exchange for some snacks and a beer he’ll do anything.”

Black laughs an evil laugh at Wilson, his beady eyes on fire, his cheeks red from laughter.

I met Black around seven times in a month. The last few times that I saw him, he said it was getting harder for him to move north. He was having difficulty passing. Because of all the Mexican groups that control the route –the Zetas, immigration, the police, and the military – the path was increasingly blocked. His way of surviving was coming to an end. His biggest problem had always been getting through Veracruz, and each time it took more work to avoid conflicts in this territory. I told him that he should just stay in Monterrey, but he laughed and said, “No. This is how la vida loca (the crazy life) is.” Words of a gang member.

“Well,” I say, “What the hell are you doing, dude, going up and down? Are you going after the dream of living on the train tracks?”

Black keeps laughing and answers, “What dreams are you talking about?”His look hardens, but he keeps laughing, and now he’s making fun of me.

“Fine,” I say.

I see Black a few more times. In these last encounters, he tells me that traveling through Palenque, Querétaro and other places has started to worry him, and he also accompanies me to get Wilson out of Don Simon’s house.

Black has vast experience dealing with the criminal underworld, but even so the paths he knew started to close to him. He had to find another way to get to Monterrey. But as I said, Black disappeared. He was a 16 year old with the experience of an old man who no longer dreams.

This is la vida corta.

EN LAS VENAS DE VIOLENCIA

En esta primera serie de dos relatos, el Colectivo Línea 84 se centra en el área fronteriza de México y Guatemala para investigar y difundir, a través del periodismo etnográfico, las complejas historias de los jóvenes centroamericanos que huyen de sus países y se convierten en parte del flujo de migrantes sin documentos y, por lo tanto, en el blanco de la creciente militarización contenida en las políticas de seguridad de norte y Centroamérica.

Específicamente, en el área fronteriza del estado de Tabasco, México y el departamento de El Petén, Guatemala la escasa protección del Estado y los actos de represión del mismo, se tejen en la vida diaria de los jóvenes centroamericanos que huyen hacia el norte. A partir de la investigación realizada en albergues para migrantes en tránsito, las vías del tren y en varios poblados fronterizos, el periodismo etnográfico se instaura como herramienta de difusión y análisis para ir más allá del reporte de eventos y se centra en los significados y el sentido que ciertos eventos cotidianos tienen en los jóvenes migrantes y en la vida comunitaria.

En los siguientes relatos, los autores complican las representaciones comunes de la migración, entrelazando la abrumadora presencia de la muerte, la experiencia del engaño, la sospecha, la desconfianza y la soledad con conversaciones puntuales y música para mostrar la máxima incertidumbre del camino de los migrantes. La vida Corta cuenta la historia del Black, un joven migrante hondureño que viajaba constantemente de su país de origen a Monterrey (en el Norte de México). Periódicamente, el Black cruzaba territorios controlados por el crimen organizado, autoridades corruptas y personas locales desconfiadas hasta que un día desapareció sin dejar rastro. En el relato Aquí todo se vende, Wilson, un solicitante de refugio de 13 años, experimenta el abuso por parte de hombres mayores en el país en el que busca protección; algunos de ellos se presentan como personas caritativas quienes buscan ayudar a jóvenes migrantes necesitados.

LA VIDA CORTA

Cerca de las tubería para tratar el agua, y donde los migrantes van a bañarse. Rio Usumascinta, Tenosique, Tabasco. Créditos Fotográficos: Irving Mondragón.

Quedé de verme con el Black, pero no llegó a nuestro punto de encuentro. Lo volví a buscar a la siguiente semana. Nada. Lo busqué por todos lados. Tenía un mes de haberlo conocido, nos veíamos regularmente y siempre llegaba. Regresé a Sueños de Oro –un pueblucho a la orilla de la carretera del Ceibo, muy cerca de la frontera con Guatemala. Estuve ahí casi cinco horas, esperé y esperé. Los chicos de las motos me volteaban a ver. Sabían que lo buscaba. Creo que al final les di un poco de lástima. El calor era intenso y yo no paraba de sudar. Cada vez que volteaba a verlos, les decía con la mirada que ahí me iba a quedar. Empezaron a secretearse algo y, finalmente, uno de ellos se puso un casco, subió a su moto, arrancó con fuerza y se paró frente a mi. Solo se me quedó viendo.

Busco al Black. “No” Me dijo con la cabeza. ¿Cuándo viene? le pregunté. Volvió a decirme que no con la cabeza. Se quitó el casco, se me quedó viendo fijo y entonces lo vi en sus ojos. Nunca llegó a Monterrey. Me dijo. Arrancó y se fue.

La vida en este camino que recorren los que migran al norte es una gran calle larga. Larga, larga y los devora. Va más allá de las fronteras y parece que no tiene fin. Por aquí caminan los que ya dimos por muertos.

Me fui. Nunca más volví a ver al Black. Seguro está muerto.

EL BLACK

Cerca de las vías del tren, Tenosique, Tabasco. Créditos Fotográficos: Irving Mondragón.

¿Cómo te llamas?

Le pregunté a un chavito con ojos de avispa que estaba escuchando a la Santa Grifa en su teléfono ¡Aaaaa chinga! Pensé. Estamos en la frontera sur de México, este morro es centroamericano y los de la Santa Grifa son de Tamaulipas. Me dio curiosidad. Tamaulipas está muy lejos y es uno de los estados fronterizos del norte de México con más de 4000 muertos por armas de fuego en los últimos 7 años. Ese estado tiene historia en todo este asunto de la migración porque es uno de los puntos de cruce fronterizo más peligrosos para las personas que van a Estados Unidos. La Santa Grifa sabe hablar de toda esa violencia aunque no hable ni de coyotes ni de albergues ni de migrantes.

El chico me respondió con cualquier nombre mientras miraba de un lado a otro, observando a la gente que iba y venía. Tenía puesta una gorra hacia atrás, unos pantalones obscuros y una playera color claro. Me senté a su lado sobre la barda del comedor. Estábamos en uno de estos albergues católicos que reciben a la gente que migra hacia los Estados Unidos y andan en tránsito por México. La mayoría de estos lugares defienden los derechos de las personas migrantes. Son unos híbridos raros de asistencia humanitaria y defensa de derechos humanos con abogados que, hoy en día, pelean casos de refugio. Con estos albergues, la iglesia católica ha ganado prestigio y poder dentro de los movimientos sociales de defensa de derechos humanos. Combina la fe y la ley para entrar al juego.

¿Para dónde vas? le pregunté. A Monterrey. Me dijo en corto. Me le quedé viendo, me sorprendí. Esa ciudad está en el estado fronterizo de Nuevo León y a pocos kilómetros de la frontera con Estados Unidos. Mucha gente pasa por esa ciudad a esperar unos días, a veces semanas, antes de moverse a los puntos fronterizos como Piedras Negras, Reynosa y hasta Nuevo Laredo para dar “el brinco” al gringo; la gente espera a que se “abra” la frontera. Para ser más claros, esperan a que les toque el turno para pasar. Las drogas y las armas generalmente también están en la lista. Pero el morrito no me dijo que iba para Estados Unidos. ¿Y a qué vas allá? le dije. Allá trabajo y luego bajo otra vez a ver a mi jaina y mi familia en Honduras.

Me quedo pensando que desde hace algunos años México se ha convertido en lugar de destino para muchos centroamericanos, algunos se establecen aquí y no porque México sea la tierra de la abundancia sino porque la gente huye a donde sea del caos que gobierna esos países. Y también la gente queda atrapada en el territorio mexicano porque hacemos el cruce a los Estados Unidos cada vez más atroz. Aquí en México las personas migrantes desaparecen, la autoridad las persigue, las golpea o terminan formando parte de los negocios criminales por decisión propia o por la fuerza; también, a autoridad migratoria mexicana detiene a las personas por tiempo indefinido en centros de detención migratorio lo que la hace parte de toda esta represión. Para acabar pronto, la justicia para todas estas personas nunca ha visto la luz. Lo que tenemos aquí son constantes “violaciones a derechos humanos”; es decir, el nombre burocratizado, institucional, formal, estilizado que ahora le damos a la violencia de Estado. El abuso del uso de la fuerza es lo que el gobierno mexicano –y también los gobiernos centroamericanos– ejercen sin clemencia. Y lo hacemos porque así dictan las políticas de seguridad regional que se imponen los desde los Estados Unidos.

Estados Unidos ha financiado y entrenado grupos especiales policíaco-militares y anti-pandillas en el Triángulo Norte Centroamericano para frenar la migración. Lo que ocurre es que estos grupos terminan persiguiendo a las personas que huyen de la violencia en Centroamérica. Mientras, México –a través de policías, agentes de migración y militares– es el filtro migratorio más grande para los gringos.

Bueno, pues Monterrey es una ciudad próspera del norte de México, y muchos centroamericanos ya han logrado establecerse ahí. Pero para llegar a esa ciudad hay que saber moverse.

Allá trabajas, vas y vienes. Es bastante peligroso andar por estos rumbos subiendo y bajando. Aquí es tierra de nadie. le dije al morrillo. Sí, mucho Zeta por Veracruz, me respondió.

Veracruz, además de Tamaulipas, es uno de los estados en donde hay más riesgos para las personas que van de camino al norte, todavía es bastión de los Zetas, quienes controlan buena parte del territorio del sur y noreste mexicano. Les hablo del famosísimo ex-brazo armado del Cartel del Golfo, cuando Osiel Cárdenas Guillén era su líder. Los Zetas es el primer grupo armado, al servicio de un cártel, compuesto por desertores de los grupos de élite del ejército mexicano: los GAFE (Grupo Aeromóvil de Fuerzas Especiales). Varios de sus miembros recibieron entrenamiento en Estados Unidos. Los Zetas también son el primer grupo que, después de la captura de Osiel, se convirtieron en la primera y más poderosa organización de mercenarios: es cierto que ya no tenían líder y tampoco los contactos para convertirse en un cartel de la droga, pero finalmente tenían algo mucho más valioso en estos tiempos; tenían en sus manos todo un gran capital: todo el conocimiento y habilidades de ejercer la violencia de manera eficiente y organizada para controlar todas las actividades ilegales o criminales lucrativas en sus territorios en un país donde la violencia también es ley. Todo esa capacidad de destrucción la utilizaron para controlar las actividades criminales que operaban dentro de los territorios que ya controlaba el cártel del Golfo. Y así incursionaron en el tráfico de personas.

Les cuento un poco. Los Zetas, para controlar el tráfico de personas, empezaron a amenazar a coyotes, guías, enganchadores y a comunidades completas que se beneficiaban del paso de la gente; los obligaron a aliarse con ellos y pagarles cuotas, tenían que convertirse en sus empleados. A quienes quisieron seguir por la libre, los mataron. Así fue como las personas que migran se convirtieron en un botín y empezaron los secuestros masivos por ahí a finales del 2008. La masacre de San Fernando es un ejemplo de su poder.

Pero mire –me dice el Black– yo ya conozco aquí como la palma de mi mano: paso por Sueños de Oro y llego hasta acá. Yo voy corriendo, voy ligero, y como les digo a esos que viene ahí conmigo. El morro voltea a ver a un trío de chavos que se les caen los ojos de marihuanos y me dice: si aguantan, me siguen sino…

Pasa gente y el morro se calla. Es prudente. Sabe que aquí todo mundo escucha todo. “Aquí ando una libra de marihuana ¿Me entiende? Aquí vengo de paso y me voy”. Te entiendo. Seguro sólo te la fumas ¿vea? Se rompe el hielo. Hablamos de la Santa Grifa. Este morro tiene 16 años y desde los 13 es pandillero de la MS. Pero no de esos que “simpatizan” o “alucinan” con alguna pandilla, no. Este joven tiene escuela, se le nota al hablar, se le nota al actuar. La clecha la lleva. Pero no es un jefe.

Cuando le pregunté por qué había salido de Honduras, me dijo en seco:

Mire. Así está el cuadro. Vivía con mi jaina. Me fui a meter a territorio de la 18 a vender droga y pisar con una de ahí. No pedí permiso para vender y ella era jaina de uno de la 18. Eso no se puede. Cuando bajo a Honduras, me pinto la boca, los ojos, me pongo una falda, una peluca y así voy a ver a mi familia y a mi jaina. No puedo estar allá mucho tiempo. Entonces me subo y llevo algo para vender y aguantar el camino.

Quién sabe si esa era toda la historia. Nunca terminamos de hablar sobre eso. Lo que era cierto es que conocía bien el camino hasta Monterrey desde Honduras. Así como todos sus peligros.

“¿Has pensado en quedarte aquí en México?” le pregunté. Sus ojos de avispa miraban para los lados. No había empezado a hablar cuando una persona se para justo a lado de nosotros. Mata la palabra al sacar el aire. Voltea a verme y me dice en voz baja: aquí no se puede hablar.

Quedamos de vernos en una semana por la mañana en Sueños de Oro, ahí a la orilla de la carretera, donde se juntan otros morros como él con sus motos.

Y por quién pregunto. Le dije.

Me mira, me clava la mirada.

Me dicen El Black.

Se da la vuelta y se va. Lo veo mientras se aleja, tiene bien bordada una “B” en su gorra.

SUEÑOS DE ORO

Las vías del tren de Salto de Agua, Mexico, cerca de la frontera con Guatemala. Créditos Fotográficos: Irving Mondragón.

Una semana después estoy en Sueños de Oro. Es un pequeño pueblo muy cerca de la frontera con Guatemala. Muy pocos habitantes, unos 300 según los datos oficiales, y muy cerca de la frontera con Guatemala. Es un pueblucho perdido al filo de la frontera. No hay nada en este lugar excepto que los migrantes pasan por aquí.

Pensé que el Black no iba a llegar después de esperar como tres horas. Pero apareció sentado en una moto detrás de uno de los morros que se reúnen en un pedacito de tierra en donde, efectivamente, estacionan sus motos a la orilla de la carretera. Así fue como empecé a conocer al Black y parte del mundo en el que viven los adolescentes que huyen a donde sea de la violencia que hay en Honduras.

Verán, desde que tenía 11 años, el Black vio muertos. Su barrio, uno de los más pobres, es también uno de los más “calientes” en San Pedro Sula. Cuenta que había días en que se desataba la “matazón” y la gente solo quedaba asustada porque sus casas estaban en medio de puro muerto. En un mismo día podía haber “un muerto en la esquina, otro enfrente, arribita de la tienda, en la otra calle y así las casas en medio de puro muerto”. Al principio se preguntaba por qué, pero aprendió rápido que eso mejor no se pregunta cuando uno muere a balazos a plena luz del día. Así empezó a ignorar la muerte y a vivir con el fin de la vida todos los días. Simplemente los cadáveres empezaron a formar parte de lo cotidiano y comenzó a ignorarlos. Después se hizo pandillero de la MS-13. Lo dice con toda naturalidad. Ser pandillero es como ver muertos todos lo días, así como la pobreza, la desigualdad, los operativos anti-pandillas, los escuadrones de la muerte y la migración desenfrenada de jóvenes que solo tienen esta aplastante realidad.

Al ser pandillero se volvió nadie para el estado hondureño y digno de ser torturado y desaparecido por policías y militares. Pero si somos más honestos, el Black, quien nunca me dijo su nombre, siempre fue nadie para el gobierno de Honduras. Siempre fue nadie para nosotros. Volverse pandillero solo permite decir que merece la peor de las muertes. A nosotros nos permite dormir tranquilos. No hay que engañarnos. Nos consuela pensar que debió ser un mártir de la pobreza; un santo sin justicia en vez de ser un pandillero que escupe en nuestra frivolidad. Ahora el Black es alguien, pero alguien que merece morir a manos de quien sea y donde sea, no importa.

Lo que pasa con el Black es que “se tuvo que alejar” de su pandilla y eso lo desterró de su país. Tuvo que huir. Entonces cruzó Guatemala y llegó a México. Subió al norte. Empezó a trabajar en Monterrey de cualquier cosa para ganarse unos centavos, salir de fiesta, comer y volver un par de días a Honduras vestido de mujer para que nadie se lo reconociera. Su vida era este camino hacia el norte y hacia el sur. Tiene las puertas cerradas en todos los países: en Honduras ya no puede quedarse y el estado no lo va a proteger; en México es un dolor de cabeza y en Estados Unidos mejor ni hablamos. Así que siempre se la ha rifado mientras se mueve. Mientras camina va vendiendo un poco de marihuana para llegar a Monterrey –el resto de la mota se la fuma.

Tiene conocidos en todo este camino, la mayoría son jovencitos como él; algunos mexicanos, otros hondureños, guatemaltecos o salvadoreños. Muchos de ellos charolean, o sea van pidiendo dinero en las vías del tren o por las calles de los lugares por los que pasan. Al Black no le gusta pedir, así que no charolea. El muchacho ojos de avispa conocía muy bien como se mueven las aguas en las vías del tren que empiezan en Tenosique; sobre todo cómo viven los jóvenes como él.

Nos vimos varias veces en ese pueblo y platicábamos mientras aguantábamos el pinche calor. “Aquí hay reglas” me decía. Los que más o menos controlan lo que sucede en las vías son los que tienen puestos de comida y cuartuchos que rentan a los centroamericanos. Ahí está Don Pepe, un hondureño de unos 40-50 años con acento cubano porque vivió mucho tiempo en Miami. Ese mira siempre desde su puesto a los caminantes que llegan. Sobre todo a las mujeres. Ofrece cuartos y la comida hondureña que vende. Les mide el agua a los que llegan, no permite que armen escándalos cerca de su lugar y su frase más conocida es “papito, aquí, nos vamoa compoltal”. No duda ni tantito en sacar un palo y quebrarse al que moleste a sus clientes o le arme algún escándalo. Tampoco duda en llamar a migración.

Enfrentito de la estación tenemos a Don Goyo, un mexicano que también renta pocilgas y vende frutas, verduras, cervezas y muy probablemente drogas a nacionales y extranjeros. Quien sabe con quién estará aliado, pero a Don Goyo le ha ido bien. Tiene un hijo que es un malandrín muy astuto y es sus ojos y oídos en la calle. Ellos aquí también controlan que los que lleguen no armen problemas, por lo menos no cerca de sus lugares. Don Goyo y Don Pepe saben y conocen, dice el Black, a todos los grupos que asaltan, violan y matan. Así es el negocio. A los jóvenes los dejan charolear y andar por ahí, pero no les gustan los vagos de ningún lado.

El muchacho de la mirada aguda conocía a muchos morros por estos lugares. Morros que uno empieza a reconocer y siempre andan por aquí. Una vez le pregunté cómo le hacían además de charolear para conseguir varo. Ya va a ver, me dijo.

Antes de que desapareciera, el Black me presentó a Wilson. Un día ese chico se nos acercó y el Black empezó a chingarlo, se botaba de risa, lo veía como cualquier cosa y le decía “¿E vo’ y como está Don Simón? jeje-jeje” Era claro que el Black se burlaba. Wilson se reía, pero volteaba la mirada a otro lado con un poco de vergüenza. El párpado derecho de Wilson casi siempre está a la mitad de su ojo. Parece que está medio drogado todo el tiempo, pero no, así es su cara. “Wilson va donde un viejo culero que vive por las vías del tren” dijo el Black “le gustan los güirros así como Wilson.” El tal Don Simón opera así: los morros pasan charoleando y entonces Don Simón les ofrece fresco, una bolsa de churros, los pone a hacer trabajitos –pasar piedras de un lado a otro– lo más inútil del mundo, y les da dinero, luego les presta la computadora para que se conecten al facebu’ y así empieza a tocarlos. “Aquí en este lugar ¡Así, mire!” me dice el Black mientras amontona todos sus dedos. “¡Montón de culeros como ese Don que buscan güirros así como Wilson! porque Wilson les da ¡e-e! Ese por unos churros y una cerveza hace cualquier cosa.” El Black se ríe con malicia de Wilson, sus ojos de avispa se encienden, sus mejillas se ponen rojas, rojas de la risa.

El Black y yo nos topamos como 7 veces en un mes. Las últimas veces que lo vi, me decía bien serio que le estaba costando trabajo subir al norte. estaba teniendo problemas para pasar; entre las bandas mexicanas que controlan los caminos por los que pasa la gente, los Zetas, la migra, la policía y los militares, al Black se le estaba cerrando el camino y se le estaba acabando la forma de sobrevivir. Su mayor problema siempre había sido pasar por Veracruz y cada vez le costaba más trabajo evitar conflictos por esos territorios. Le dije que se quedara en Monterrey, pero se rió y me dijo “No. Así es la vida loca”. Palabra de pandillero.

Bueno, le digo, y tú cabrón ¿qué putas haces de arriba para abajo? ¿andas persiguiendo el sueño de vivir en las vías?

El Black se sigue riendo y me responde “¿De que sueños me habla?”. La mirada se le hizo dura, continua con su risa, ahora se burla de mi. Bien, le digo. Todavía vi al Black varias veces. Me acompañó por Wilson a casa de Don Simón en otras ocasiones. Sus andanzas en Palenque, Querétaro y otros lados lo dejaban cada vez más preocupado. El Black tiene una experiencia inmensa lidiando con todos los malandrines de los alrededores, pero aún así los caminos que conoce se le empezaban a cerrar. Tenía que buscar otra forma de llegar a Monterrey. Pero como ya les dije, el Black desapareció, era un morro con la experiencia de un viejo sin sueños. Sólo tenía 16 años.

Así es la vida corta.