Arizona State University-West

Though largely unrecognized by official planning instruments and unacknowledged by the public in anti-immigrant Arizona, immigrants are transforming metropolitan Phoenix. Visualizing Immigrant Phoenix, a student-faculty research collaborative I direct at Arizona State University, explores these transformations by engaging its audience through vibrant visualization of immigrants’ imprint upon the Phoenix urban environment. This project occurs at a time when immigrants are increasingly demonized, criminalized, and denied due process. Our work responds by according due importance to migrants’ creative and deliberate impacts on everyday urbanism in transnationalizing cities.

In an era of unprecedented human mobilities, Phoenix diversity is not unexpected for a major American city. Current US Census data shows 20% of city residents are foreign born, 65% coming from Mexico, and 41% of the city population is Latinx. Stymied by reigning anti-immigrant sentiment, city residents and civic leaders are reluctant to acknowledge—let alone cultivate—creative ways that migrants already influence the city as informal, unintentional urban planners-from-below. Our projects track the ways in which immigrants have revived stagnant neighborhood economies, brought magical-realist redesign to the cityscape, added colorful flair to the city’s subdued design palette, infused global youth practices, and transnationalized Phoenix urbanism with local outcroppings of global religions, cuisines, cultures.

Immigrant and diaspora youth in particular play a critical role in bringing this realization into view. Our youthful team of undergraduate researchers brought fresh perspectives from their own migrant and diaspora communities. The inclusion of a Somali refugee, a first-generation Assyrian-Iraqi, and a Mexican DACA recipient this past spring extended the project’s reach and depth of insight. Although our gaze is not exclusively directed at youth, young migrants frequently do become central to our inquiry as team members engage their own networks to pursue their research.

Origins of the Project

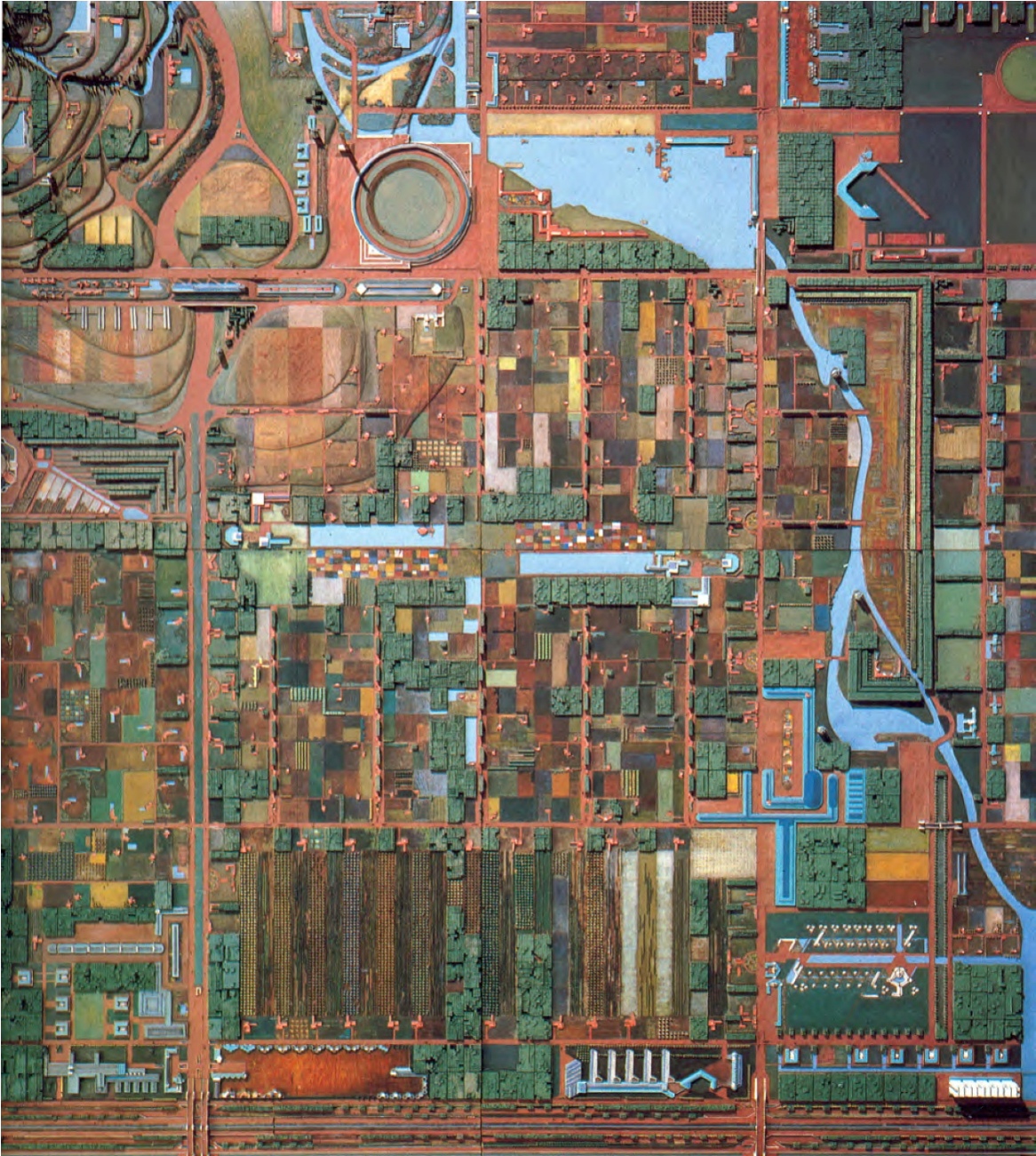

Billboard in central Phoenix neighborhood (2012), Kristin Koptiuch

Visualizing Immigrant Phoenix is an extension of my long-term commitment to teaching, researching, and visualizing the impact of immigrants on metropolitan Phoenix, where I’ve lived for 25 years. Having taught courses on migration and worked with migrant advocacy organizations, I began to create ethnographic photo essays to defuse Arizonans’ hyper-sensitivity toward immigration, integrating emotion and affect with a resistant critical gaze (e.g. “Cruzando Fronteras/Crossing Phoenix,” 2012). To integrate students into these initiatives, I successfully applied for modest funding through a unique student-faculty research program offered by ASU’s New College of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences, which provides student teams with a budget of $500 and modest student stipends or two academic credits.

Thus far we have completed some two dozen photo essays and curated photo sets, accompanied by short descriptive and analytical ethnographic narratives. Researchers submitted drafts of their essays and photos, and revised them in response to my editorial comments and suggestions into finished projects, showcased on our website. At once visually stimulating and thought-provoking, we sought to share them with “live” audiences in a manner that preserved the immersive, visually rich digital format of the website presentations. We’ve experimented by creating an exhibition of our urban visual ethnography project, anchored by enlarged photos that capture the project’s key themes (immigrant portraits, artifacts, events, neighborhoods, businesses, landscapes).

Exhibit at Arizona State University-West (2017), Kristin Koptiuch

Presented first at the 2017 Society for Applied Anthropology conference in Santa Fe and then at our own West campus of Arizona State University, the exhibit also includes video shorts, sonic atmospherics, live website projection, a portfolio of printouts of individual projects, banners, promo materials, and QR codes that take viewers’ mobile phones straight to the website. To better engage our audience, we took seriously the truism that, welcome or not, “we are all immigrants.” Our interactive portrait booth (now featured on our website) drew an enthusiastic response from over 100 visitors who declared their solidarity as immigrants and their descendants.

Youth Circulations in Phoenix

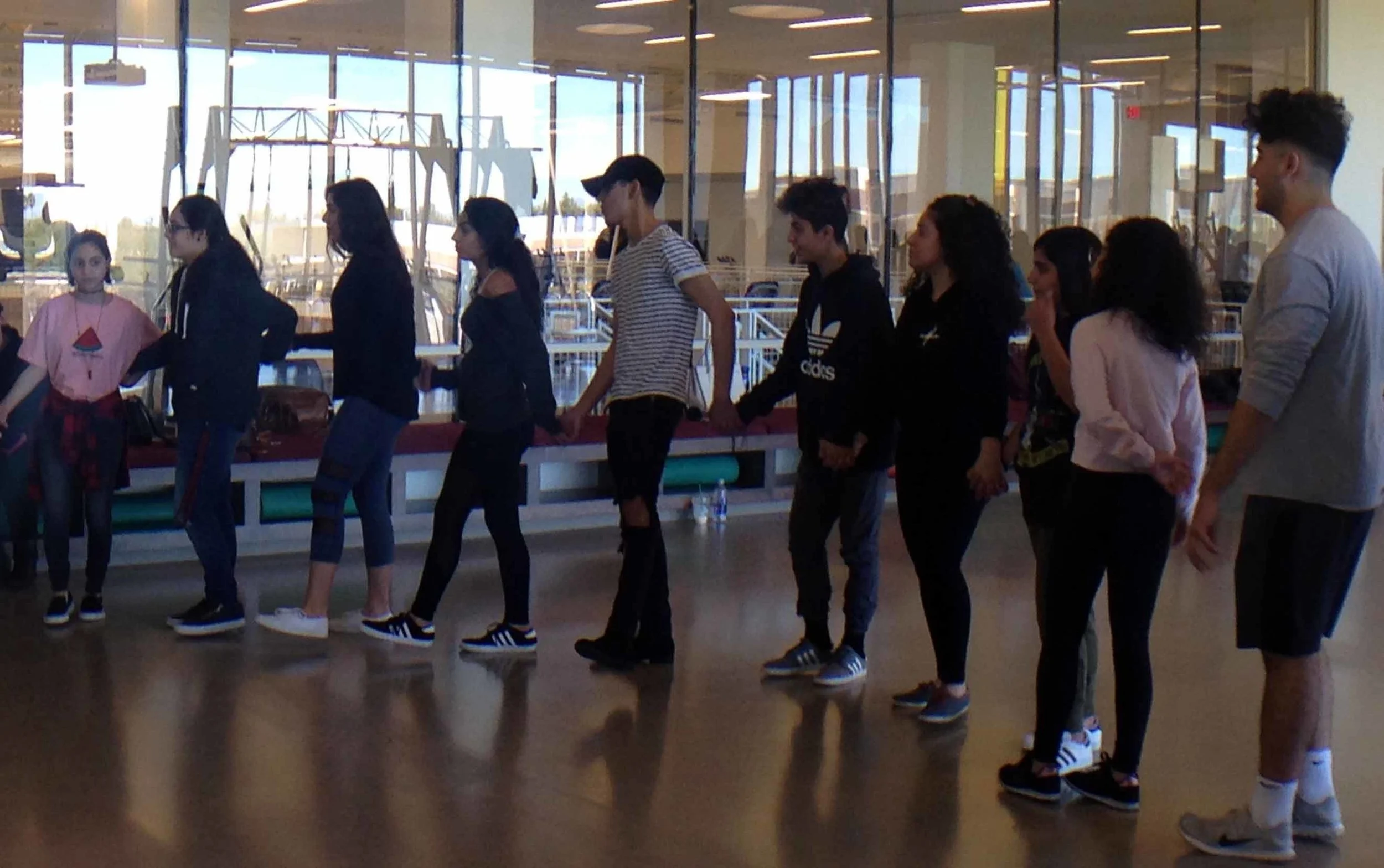

Folkdance class, Assyrian Student Association of Arizona, Crystal Cespedes

Several of our stories track young migrants as they circulate through the city and beyond. For instance, many Iraqi refugees have resettled in metro Phoenix over the last 20 years, including Assyrian and Chaldean Christian minorities. Crystal Cespedes’ interview with a first-generation US-born Assyrian leader of the Assyrian Student Association of Arizona briefly unpacks the origins of Assyrian ethnics in Phoenix and highlights the importance accorded to education and cultural preservation by the student club at Arizona State University, through peer instruction of folk dances to traditional music.

Teaching modern Aramaic, Ileen Younan

The preservation of Assyrian language and history is also foregrounded in Ileen Younan’s piece on instruction in modern Aramaic by a young Iraqi-born teacher to first-generation children through their community church. The church also offers Aramaic education to older Assyrian youth like Younan herself, so they can learn to write and speak their parents’ native language.

Feast at weekly Iraqi family gathering, José Grijalva

José Grijalva’s visit to a weekly family gathering at the home of an Arab Iraqi classmate introduced him to Arab culture, language, and cuisine. Significantly, the lively family interactions and mountains of Middle Eastern food resonated with Grijalva’s experiences at his own Mexican American family’s cookouts in the Arizona border town where he grew up.

Phoenix is also home to post-colonial British diasporic communities whose youth perpetuate their parental legacy in the sport of cricket, an under-represented sport in what is otherwise a highly sports-conscious city. Hussein Mohamed’s short video introduces us to several immigrant and first-generation Pakistani team members of the Arizona Stallions Cricket Club. This is one of 18 Phoenix cricket teams comprised largely of immigrant youth hailing from cricket-playing nations like Sri Lanka, Jamaica, Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, and South Africa. Interviews recount team members’ association of cricket with their families’ immigrant homeland roots.

Cricket match in Phoenix, Hussein Mohamed

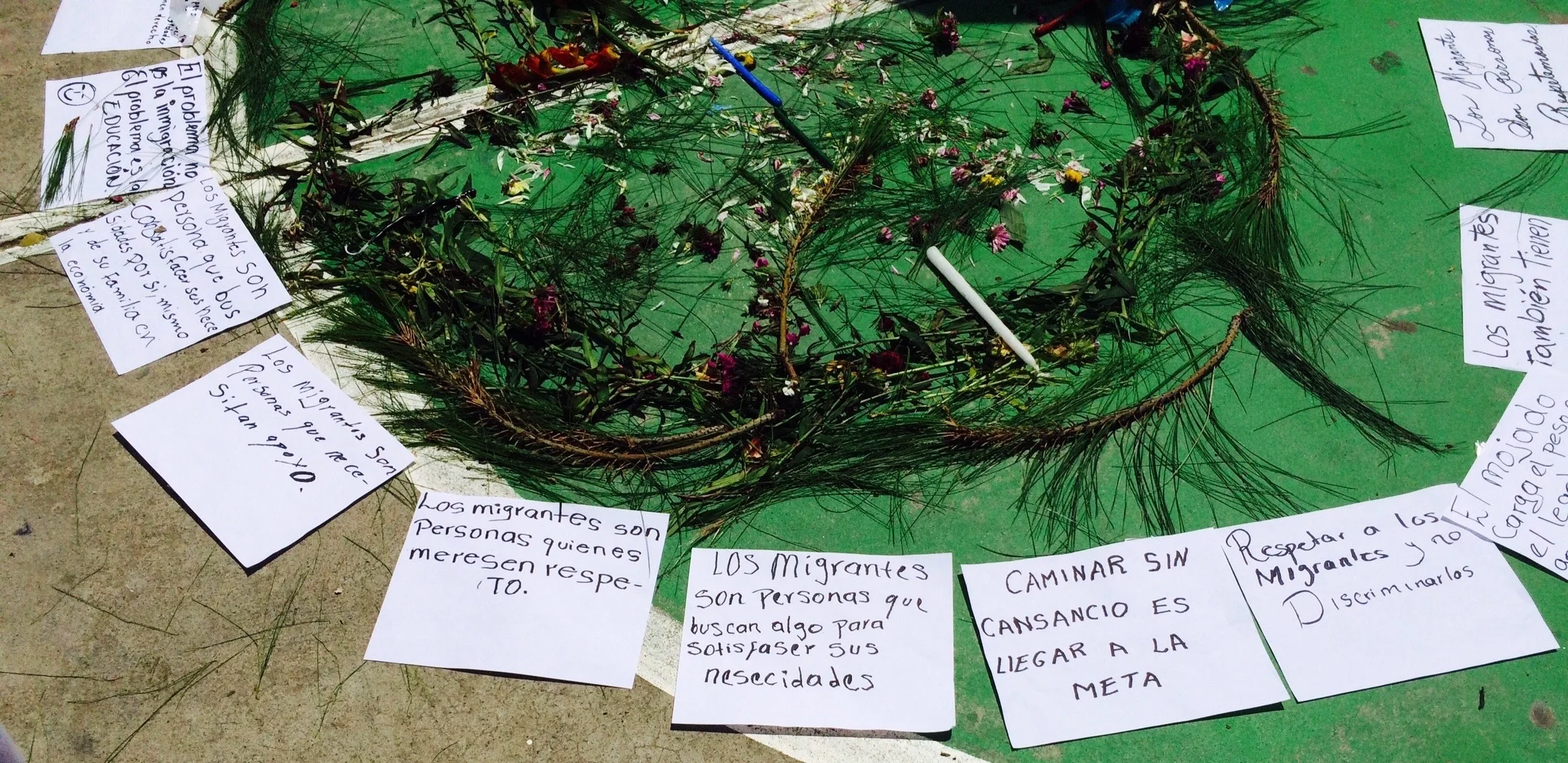

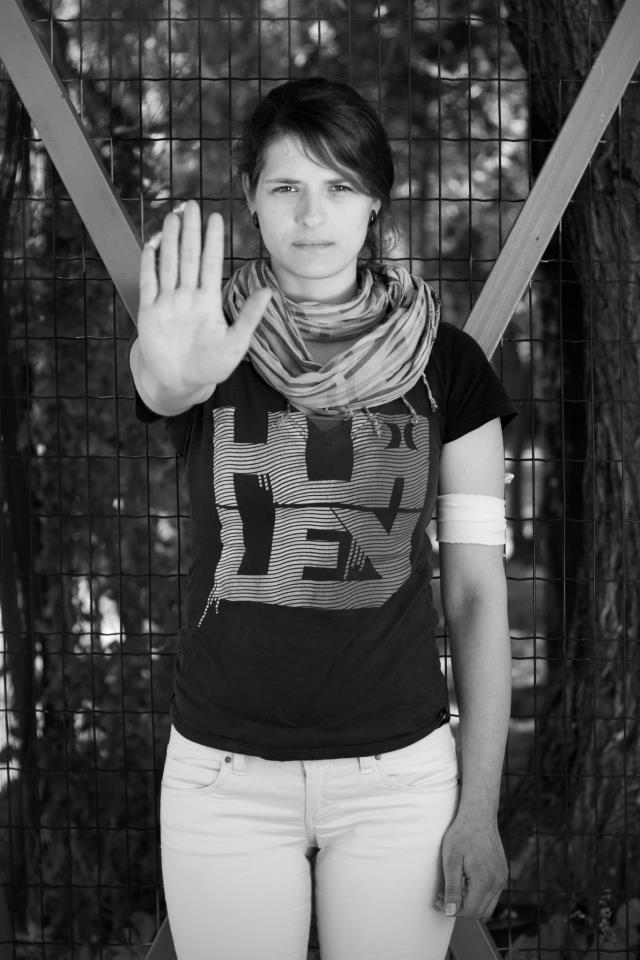

DACAmented youth struggle for belonging and identity, Argenis Hurtado Moreno

As is well known, not all migrant youth have the luxury of open visibility. Argenis Hurtado Moreno invites us to hear the stories of two Mexican DACAmented youth, aka DREAMers, who struggle for belonging and identity in the America that enculturated them throughout their youth but stigmatizes them as young adults and legally excludes them from a pathway to citizenship. The two women interviewed express a palpable frustration and sense of injustice toward the nation that refuses to accept them as the exemplary made-Americans that they know they are.

Mexican pointy boot, José Grijalva

While doing fieldwork at Mercado de los Cielos, a Mexican makeover of a defunct mall anchor department store, José Grijalva was entranced by an elongated-toe boot on display at a shop selling Mexican cowboy boots. In sleuthing out the meaning this cultural artifact, Grijalva discovered that the Mexican pointy boot links transnational youth circulations on both sides of the US/Mexico border. Dance crews don custom-made boots with points as long as seven feet, offset by color-coordinated skinny jeans and cowboy hats. They perform choreographed steps to a recent style of Mexican music called Tribal, mixing Aztec and African sounds over a cumbia baseline, the DJ tapping into multi-ethnic and autochthonous Mexican roots that may carry special appeal to migrants far from the homeland. These dance competitions are popular in Dallas, Texas, as many Mexican immigrants there come from the state of San Luis, where Tribal is popular. Clearly, the pointy boot is an element of Mexican subcultural style that has easily crossed the border.

The Power of Migrants and the Subversion of the Community[i]

Through the subtle subversion of depicting these everyday migrant crossings and contributions, Visualizing Immigrant Phoenix seeks to intervene in the public perception of migrants in Phoenix. Our stories of migrant youth depict them as resilient as they are vulnerable. Youth are the site of intensive parental investment for perpetuating immigrant cultures, languages, histories (Heidbrink 2014). Yet migrant and diaspora youth connect as fluidly with local practices as they import transnational styles and fads through music, fashion, dance, relationships. Thus, they complicate simplified notions of “preserving” cultural forms. They cross virtual transnational bridges that span the spaces of their daily lives, rendering a subversive ordinariness to crossing borders (Leurs 2015). Their American dreams are defiant, insisting upon the legitimization of all of their global identities (Dissard & Peng 2013).

Visualizing Immigrant Phoenix’ collaborative ethnographic photo essays offer a visually rich counter-narrative to the intensifying discourse of fear promulgated by current instabilities in national and state immigration policies. By centering on migrants’ everyday mobilities, our critical visualization strives to (re)move walls and expand the appreciative embrace of immigrants in our city’s collective gaze.

Works Cited

Arau, S., Arizmendi, Y., & Guerrero, S. (2004). A Day without a Mexican. Televisa Cine.

Dissar, J. and G. Peng. (2013). Documentary: I Learn America. http://ilearnamerica.com/

Heidbrink, L. (2014). Migrant youth, transnational families, and the state: Care and contested interests. University of Pennsylvania Press.

James, S., & Dalla Costa, M. (1972). The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community. Consultado el, 5.

Leurs, K. (2015). Digital passages: Migrant youth 2.0. Diaspora, gender and youth cultural intersections. Amsterdam University Press.

[1] This subtitle evokes the transformative, classic feminist treatise, The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community (1972). Mariarosa Dalla Costa and Selma James argued that the centrality of women’s domestic work to the social reproduction of capitalist relations generating surplus value makes women key subversive protagonists in the struggle to re-appropriate the social wealth they produced. Migrants now are similarly positioned; its jokiness aside, films like A Day Without a Mexican (Sergio Arau 2004) show us that popular culture has already grasped the potential subversive power of migrants.

Kristin Koptiuch is a cultural anthropologist and urban ethnographer who tries to practice anthropology as much performance art as social science. She is associate professor of anthropology in the School of Social & Behavioral Sciences at Arizona State University-West.