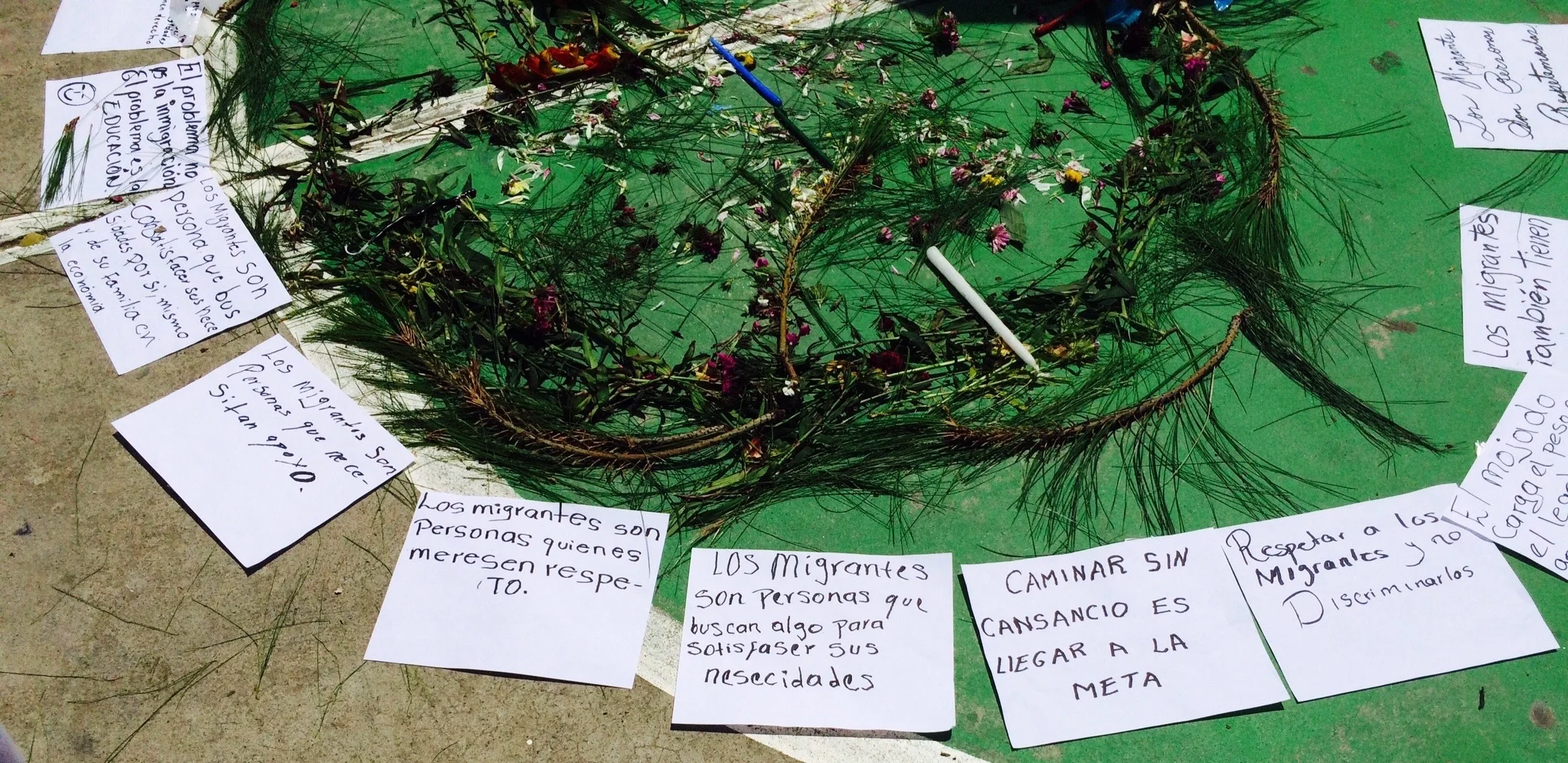

El contexto de este poema surge a través de las múltiples vivencias de sabidurías compartidas por mujeres, hombres, niñas, niños, jóvenes, ancianos y ancianas durante la investigación de campo sobre migración en Almolonga realizada en el verano del 2016 en Guatemala.

Describe en su forma orgánica la vida de una familia agricultora de Almolonga que se levanta aproximadamente a las 2:00 a.m. y termina su día laboral alrededor de las 7:00 p.m. Por consiguiente, la narración de este poema está dividida en las horas que rigen la dinámica agrícola de la población de dicho municipio.

Las primeras tres estrofas consisten en un cuestionamiento sobre la vida que lleva la familia actualmente y las últimas dos la solución que resuelven tomar. Cansados, la pareja decide migrar a los Estados Unidos.

Ellos narran su viaje. En el sexto verso, la escritora narra en tercera persona, describiendo la voz callada de muchos migrantes que han desaparecido sin saber de ellos.

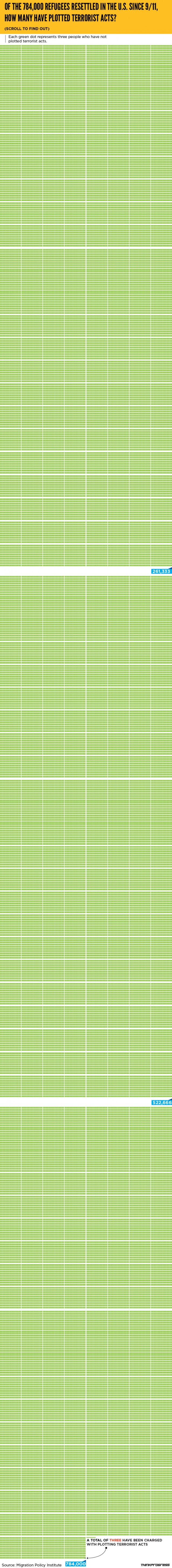

Escrito en Español, K’ iche’ e Inglés, este poema es dedicado a las miles de personas que migran, asumiendo los costos diarios y humanos de la política exterior de los Estados Unidos.

************************************************************************************

The context for his poem emerges from the many life experiences of shared wisdom by women, men, children, youth and elders that resulted from conducting fieldwork on migration in the Summer of 2016 in the municipality of Almolonga, located in the western highlands of Guatemala.

The poem organically describes the life of an agricultural family in Almolonga who wake up approximately at 2:00 a.m. and end their work day at about 7:00 p.m. Accordingly, the narration of this poem is divided into the hours that coincide with the agricultural cycle of Almolonga.

The first three stanzas question the family’s present-day life and the last two are about their resolution. Tired, the couple in the poem decide to migrate to the United States.

They narrate their trip and journey north. In the sixth verse, the author narrates in third person describing the silenced voices of many migrants who have disappeared and whose whereabouts are unknown.

Written in Spanish, K’iche’ and English, this poem is dedicated to the thousands of people that migrate, bearing the everyday human costs of US foreign policy.

Botas Negras

2:00 a.m. (Aún no ha salido el sol)

Yo no necesito reloj para levantarme.

Solo siento el olor de mis botas negras para recordarme.

Yo no necesito ver la tierra para sentirla.

Solo necesito mis manos,

para limpiarla, sembrarla, picarla y cosecharla.

6:00 a.m. (Mercado Local vs. Mercado Global)

Yo no necesito que me repitan que los precios de las verduras han bajado.

Solo necesito llevar mi bulto al mercado.

Yo no necesito que ella me vea los ojos cansados,

para saber que estamos bien ‘pisados.’

7:00 a.m. (Retorno a casa)

Yo no necesito que me digan que a Diego, Martita y Juanito les hace falta alimentación y educación.

Y que mi casa no vale un millón.

Que la operación sale en Q. 20,000.00.

No necesito que me digan en que me van ayudar.

Yo ya lo pensé, lo soñé y lo sé.

9:00 a.m. (El hogar y la decisión final)

Y la vi y me vio y nos vimos.

Y supimos.

Y nos fuimos.

10:00 a.m. y semanas… (La ida)

Caminamos y sudamos

por el Desierto.

Recordamos y lloramos

por el Rio.

Y se la llevaron y me dejaron.

Y lo triste es que nunca llegaron.

Tuqxajab’ q’eq

Keb’ kajb’al (Le q’ij maja kiloq)

Chi kinwalijik in rajawaxik ta’ chwe kajb’al.

Xaq xu kina’ le raxlab’ le nutuqxajab’ q’eq’ab’ che kanataj chwech.

In rajawaxik taj kin wil le ulew che kin na’o.

Xaq xu rajawaxik le nuq’ab’,

che usu’ik, tikonik, k’otinik xuquje’ uyakik.

Waqib’ kajb’al (K’ayb’al Chutin ruk’ K’ayb’al Nim)

In rajawaxik ta’ chwe che kanataxik che le rajil le uwach ulew che xqajik.

Xaq xu tane’ kinkamb’ik le nutanat pa le k’ayb’al.

In rajawaxik ta’ chwe che are’ kuril le nub’aq’och kosinaq,

che retanla’ che ujk’olik pa k’axk’ol.

Wuqub’ kajb’al (Tzalajem pa ja)

In rajawaxikta’ chwe che kab’ixik che ri a Tek, laj Marta’ xuquje’ laj Xwan che rajawaxik chake che ketzuqik xuquje’ le pixonem.

Che le wachoch che marajil ta’ jun millón.

Che le kunab’al kil Q. 20,000.00.

Rajawaxik ta’ chwech che kab’ix chweche kinkito’.

In xinchomaj, xinwichik’aj xuquje’ wetam chik.

B’elejeb’ kajb’al (Le ja xuquje’ ri chomanik k’isb’al)

Xinwilo, xinrilo, xaqil qib’.

Xaqetamaj.

Xujek.

Lajuj kajb’al - Q’ij rech wuq’ij… (Ilem)

Xujb’inik xuquje’ xujil pak’atanal

choch le zanib’ Ulew.

Xanataj chaqe xuquje’ xujoq’ik

choch le Plo.

Xk’amb’ikxin k’iya’y q’anoq.

Le b’isonik che man xeb’opanta’ wi’.

Black Rubber Boots

2:00 a.m. (Darkness)

I don’t need a watch to wake up.

I only need the smell of my black rubber boots to remind me.

I don’t need to see the earth to feel it.

I only need my hands,

to clean it, to sow it, to reap and harvest it.

6: 00 a.m. (Local Market vs. Global Market)

I don’t need to be reminded that the prices of vegetables have lowered.

I only need to take my bundle to the market.

I don’t need her to see into my tired eyes,

to know that we are ‘fucked.’

7:00 a.m. (Going back home)

I don’t need to be told that Diego, Martita and Juanito need food and education.

That my house is not worth millions.

That the operation is going to cost 20,000.00 quetzales.

I don’t need your help.

I already thought about it, I dreamt about it and I know it.

9:00 a.m. (The house and the final decision)

I looked at her, she looked at me, we looked at each other.

And we knew.

And we left.

10:00 a.m. and weeks… (The departure)

We walked and we sweated

through the Desert.

We remembered and cried

through the River.

And they took her and they left me.

And the tragedy is that they never arrived.

Amparo Monzón is a Maya K’iche’ woman and holds a M.A. in International Relations from the University of Westminster. She is passionate about learning and sharing experiences.

For the previous blog in the series: Lauren Heidbrink: Migration and Belonging: Narratives from a Highland Town/Migración y Pertenencia: Narrativas de un pueblo del altiplano/

For the next entry in the series: Sandra Elizabeth Chuc Norato: Deudas y Migración: Explorando a la realidad de Almolonga/ Debt and Migration: Exploring Almolonga’s reality