By Sarah J. Diaz and Jenny Lee

The Trump Administration’s policy of family separation cannot be accepted as a legitimate government immigration policy. Instead, it is imperative for the global community to recognize that the policy of family separation, and the manner in which parent-child separations were carried out, constitute crimes against humanity.

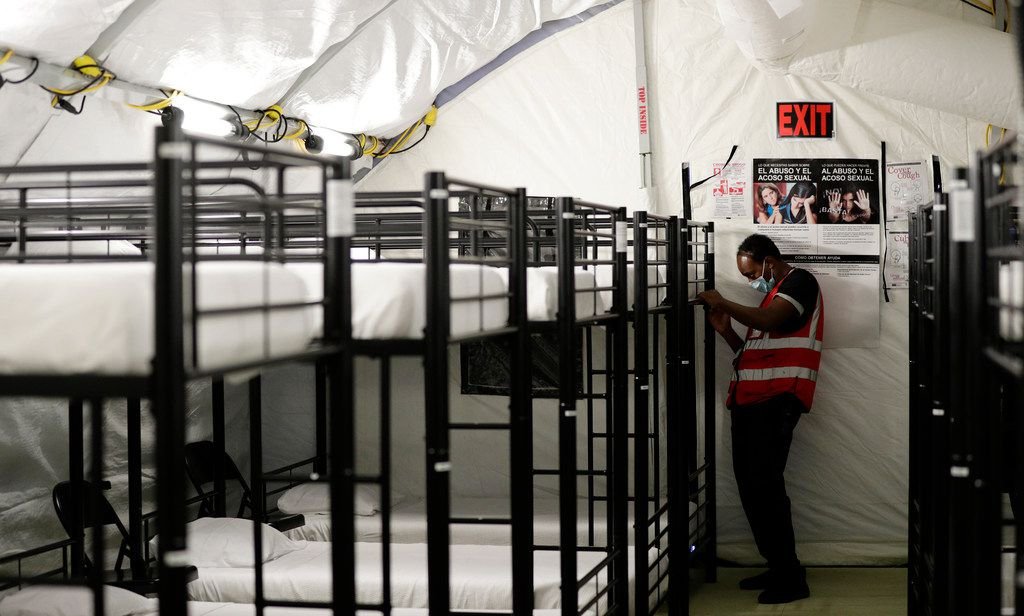

AP Photo/Dario Lopez-Mills

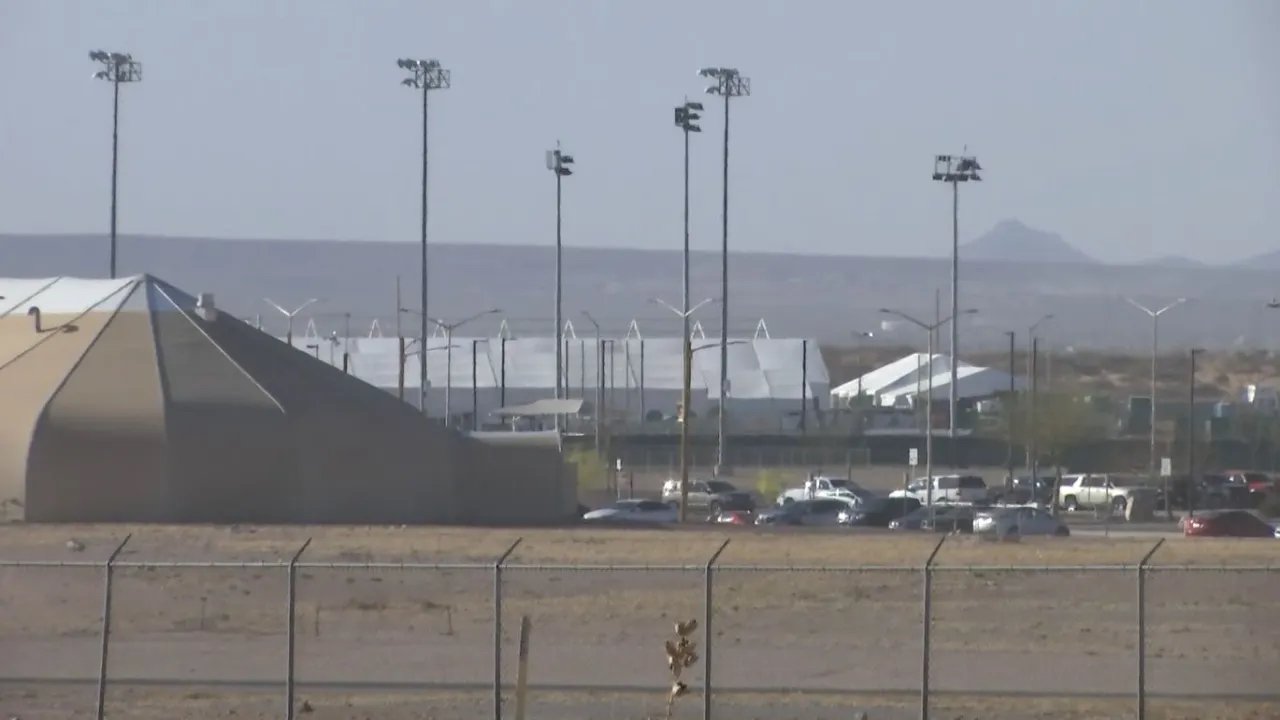

In the spring of 2018, United States citizens bore witness to the unfathomable: children, toddlers, and even breastfeeding infants were ripped screaming from their parents’ arms by U.S. immigration officials and then disappeared into government detention. The events that took place shocked the collective conscience, moving American mothers to march with their children to government immigration offices across the country to demand a halt to the program.

The policy of family separations, or parent-child separations, was formally announced by the Trump Administration through a memo entitled “Zero Tolerance” and defended by the administration as not only permissible but required by U.S. law. The Biden Administration condemned the phenomenon as a “human tragedy that occurred when our immigration laws were used to intentionally separate children from their parent or legal guardians (families).” However, there have been no pronouncements by the Biden Administration that the Zero Tolerance policy was anything other than a legitimate, albeit unfortunate, immigration policy.

Documenting crimes against humanity

The Columbia University's Center on Mexico and Central America (CeMeCA) published the report as part of their Regional Expert Series entitled Zero Tolerance: Atrocity Crimes against Migrant Families in the United States: An Accountability Framework for Family Separation. The report synthesizes data gathered from litigation, Freedom of Information Act requests, and publicly available reports written by nongovernmental organizations, government bodies, and international organizations to determine how the Trump Administration’s policy of family separations unfolded.

The review found that the Trump Administration implemented the policy of family separation under Zero Tolerance with the specific intent to deter migration from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. Critically, the report found that terrorizing children and families through parent-child separation was central to the Trump Administration’s policy, not merely an unfortunate byproduct. The report found that the Trump Administration was at all times aware of the grievous and lasting harm that the family separation policy would cause to children, and that the administration exploited harm to children to employ pervasive illegal coercive practices to force deportations of separated families. As of the date of the report’s publication, the Trump Administration separated over 5,500 children from their parents; however, an accurate number will never be known.

The report’s factual findings indicate that the acts carried out by the Trump Administration to effectuate parent-child separations via Zero Tolerance constitute the crimes against humanity of persecution, deportation or forcible transfer, torture, and other inhumane acts under Article 7 of the Rome Statute, the statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC). The report finds that these crimes against humanity fall within the jurisdiction of the ICC. While the U.S. is not party to the Rome Statute, the ICC has held that it may exercise jurisdiction over certain transboundary crimes, including deportation, persecution, and other inhumane acts, which are initiated or completed in a state that is party to the Rome Statute (this includes all countries in the Central American Northern Triangle).

The Office of the Prosecutor for the International Criminal Court Must Act.

Source: ACLU, Family Separation: By the Numbers (Oct. 2, 2018), https://www.aclu.org/issues/family-separation

While the Biden Administration created a Task Force to enable the reunification of children separated from their parents, there is no indication that the U.S. government intends to pursue accountability nor institute an effective prohibition on the use of parent-child separations in the future. The ICC Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) has stated that there is “a strong presumption that investigations and prosecutions of crimes against children are in the interests of justice,” and that wherever the evidence permits, the ICC “will seek to include charges for crimes directed specifically against children.” Thus, the report recommends that the situation of family separation pursuant to the Zero Tolerance policy be investigated by the OTP. The report also calls upon the Biden Administration to appoint a special prosecutor in conjunction with the U.S. Attorney General to investigate avenues for domestic criminal accountability, and to make every effort to immediately restore the victims of crimes against humanity, including reunifying and providing compensation to the families who have suffered and continue to suffer from separation under Zero Tolerance.

We hope this framework for accountability can facilitate a new dialogue on behalf of separated families - recognizing that family separation was not merely a law enforcement tool subject to abuse, but an act of state violence that must never be perpetrated again.

The learn more, please read the full report.

About the authors

Sarah Diaz, J.D. LL.M.is the Associate Director of the Center for the Human Rights of Children and Lecturer in the School of Law at Loyola University Chicago. Professor Diaz has worked at the intersection of child migration and human rights for fifteen years, working with NGOs on complex human rights, migration, and international criminal law issues.

Jenny Lee, Ph.D. is a Research Assistant at the Center for the Human Rights of Children and a 3rd year law student at Loyola University Chicago School of Law. She is a former educator and higher education administrator who has worked in nonprofit organizations serving immigrant women, children, and elderly who are victims of domestic violence.

![One of the many poster sheets used to brainstorm ideas with the youth group on the issue of how HIV mattered to them. [Photo taken by Susan Frohlick.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5409165ce4b020fb2b163b62/1628690241588-TOYJWG1JKKQQAIR2PPMC/figure+1.jpeg)

![Led by Bonface Beti, the youth are using playback theatre techniques to translate their experiences into performance mode. [Photo taken by Susan Frohlick.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5409165ce4b020fb2b163b62/1628690436850-15J7MVKQ602S30CQE5B2/Figure+2.jpeg)

![Performing the skit at the HIV Awareness Community Pop-Up Event Presented by African Youth held at Central Park, Winnipeg, on September 30, 2017. [Photos taken by Paula Migliardi and used with permission.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5409165ce4b020fb2b163b62/1628690611274-42JB9UTO7IJ83UYKFBZW/figure+4.jpeg)